Monthly Archives: June 2023

Hospitality-Simply Another Word for Gospel

FIFTH SUNDAY AFTER PENTECOST

Prayer of the Day: O God, you direct our lives by your grace, and your words of justice and mercy reshape the world. Mold us into a people who welcome your word and serve one another, through Jesus Christ, our Savior and Lord.

“Whoever welcomes you welcomes me, and whoever welcomes me welcomes the one who sent me.” Matthew 10:40.

Jesus presumes on hospitality. Success of the mission upon which he sends his disciples in the verses previous to our reading depends on their finding a welcome among the people they meet. Jesus expects that his disciples will be welcomed by the curious, the generous, the hopeful and open minded. He is counting on hospitality.

In this respect, Jesus is thoroughly grounded in traditions of the Hebrew Scriptures. At the dawn of history Abraham and Sarah welcomed three strangers travelling in the heat of the day with shade, water for their tired feet and the best meal of which they were capable. They had every reason ignore or turn away these visitors. The world was a dangerous place during the bronze age. For all they knew, these three strangers might have been bandits or representatives of the nearest city state come to run them out of the jurisdiction. Instead, they opened their home, their larder and their hearts and, as the author of the New Testament Letter to the Hebrews tells us, ended up “entertained angels without knowing it.” Hebrews 13:2.

Of course, Jesus is well aware that he is sending his disciples out into an inhospitable world. Alongside the example of Abraham and Sarah is that of Sodom and Gomorrah. The citizens of these two towns met the same strangers so lavishly entertained in the tent of Sarah and Abraham with threats of gang rape. Jesus knows that his disciples will be “sheep into the midst of wolves.” Matthew 10:16. He warns them that they “will be hated by all because of my name.” Matthew 10:22. The disciples can expect that their good news will be met with rejection. They can expect that doors will sometimes be slammed in their faces. They are not to be dismayed, nor are they to seek retribution. They simply move on to the next town. What might the church of today look like if only more missionaries of the 19th and 20th Centuries had taken the same approach rather than riding the coattails of colonialism?

Hospitality to strangers is an integral part of the church’s life. As noted above, the Letter to the Hebrews urges us to “show hospitality to strangers.” Hebrews 13:2. Saint John commends Gaius the elder for welcoming, housing and providing for strangers. III John 5 Throughout the Middle Ages, monasteries afforded hospitality to pilgrims, travelers and the wandering homeless. Today refugee sponsorship and resettlement are important ministries of the church-and increasingly so given that, as of the end of 2021, no less than 89.3 million people were forcibly displaced worldwide as a result of persecution, conflict, violence and human rights violations. USA for UNHCR Website.

It is against this back drop that I wish to reflect on two events that transpired over the last couple of weeks. One was the tragic loss of the Titan submersible in which five people were lost. The other was the sinking of a packed migrant boat off the coast of Greece in which at least seventy-nine people were lost and dozens more missing. In the case of the submersible, which was carrying four billionaires and a nineteen-year-old son of one of them, the United States Coast Guard and governments from around the world conducted an extensive search sparing no expense and employing the most advanced equipment. The migrant boat received aid only after it had gone down, having previously been seen in distress. The fate of the submersible was televised non-stop by all major news outlets. The migrant tragedy got only a passing notice. Sadly, while the loss of the submersible was a unique event affecting a few adventurers who willingly assumed a substantial risk, the fate of the migrants off the Greek coast is but one among many such tragedies affecting thousands of individuals whose decision to put to sea had little to do with thrill seeking and everything to do with a desperate effort simply to remain alive. The juxtaposition of these two shipwrecks makes painfully clear which lives matter and which do not; which deaths are newsworthy and which are not significant enough to make the obituaries.

We are reminded by these events that the world today is no more hospitable to sojourners, refugees and aliens than it was in the days of Abraham and Sarah. The hardline stance of Europeans and North America against migration from Africa in the fist instance and Central and South America in the case of the United States has left persons threatened by war, gang violence and starvation little choice but to embark on dangerous journeys by land and sea in the hope of finding sanctuary. The cruelty of these policies rivals that of Sodom and Gomorrah. We who stand on what we deem our side of the border would do well to contemplate the fate of those two cities and consider whether we are not earning for ourselves the same judgment. God has a particular concern for the refugee, the stranger, the people without a country. See Psalm 107:4-9; Leviticus 19:33-34.

There is a reason why hospitality to strangers has been woven into the fabric of Torah and constitutes a core practice of the church. It is simpy another word for “gospel.” As we learn from the book of Genesis, all human beings spring from the same descendants, share the same blood and are all alike made in God’s image. As the Book of Revelation makes clear, it is God’s intent to reunite the human family in a new creation consisting of every tribe, nation and tongue under heaven. In addition to embodying the practices of Jesus, the ministry of hospitality serves as a witness to the gentle reign of God Jesus proclaims and God’s gracious will that God would have done on earth as in heaven. Jesus tells us that one criterion under which the nations of the world will be judged is the degree to which they welcome strangers. Matthew 25:35. As the visible presence of Christ’s Body on earth, the people of God are to live into God’s future. The people of God are to be, in the words of Clarence Jordan, founder of Koinonia Farm, a demonstration plot for God’s kingdom. Jesus teaches us that hospitality invites transformation, builds trust, births friendship, overcomes prejudice and extends visit by visit the just, gentle and peaceful reign of God. To reject the stranger is to reject Christ, resist the work of the Holy Spirit and rebell against God’s gracious will for creation.

It is for this reason that we sponsor, resettle and assist refugees and migrants seeking entry into our country. That is why we advocate for open borders. It is why our churches seek to become places of sanctuary and safety for LGBTQ+ folk in states that have adopted violent, repressive and discriminatory laws that put them in jeopardy. It is why we strive to remove from our worship, language and practices all that would become a stumbling block for someone who might be open to Jesus and the kingdom he proclaims. As the GEOCO commercial says, “it’s what you do” when you follow Jesus.

Here is a poem by Remi Kanazi from the perspective of the refugee, stranger, sojourner, outcast.

Refugee

I.

she has never

seen the sea

sunlight imprinted

on her father’s skin

waves crashing

at his feet

smile tattooed

underneath boyish grin

snapping pictures

with closing eyelids

her father’s face

flush on recollection

the same waves that had

clenched like an angry jaw

at his mother pushed him

forward like a train car

watched his neighbor drown

tears streaming

eyes connecting

screams muffled

as inhalation

suffocated lungs

muscles weary

skin pruning

barely a boy

knowing he would

never return

his neighbor

an older man

born in Akka

looked dapper

at dinner parties

looked helpless that day

his body revolting

against death

a pool intent

on swallowing him

so many stroking

to get on boats departing

who’d have known this gulf

would be their deathbed

II.

she has been beaten

ID checked

body thrown to the ground

fists and feet pummeled

fractured hip, shoulder broken

heart, too many times

tear gas inscribed on her lungs

she wrote back on her breath

that the canister’s defeat is near

III.

these fields are ours

she told me

before the Europeans

and Brooklynites

before the swimming pools

army jeeps and barbed wire

before the talks, roadmaps

and Swiss cheese plans

before declarations rewrote history

those hills met footprints

and that can’t be erased

like village massacres

can’t be erased

like broken bones policies

can’t be erased

like the screams ringing

in her father’s ears

can’t be erased

we are the boat

returning to dock

we are the footprints

on the northern trail

we are the iron

coloring the soil

we cannot

be erased

Source: Before the Next Bomb Drops: Rising Up from Brooklyn to Palestine, Remi Kanazi (c. Haymarket Books, 2015). Remi Kanazi (b.1981) is a Palestinian-American poet, writer and community organizer currently living in New York City. He is the editor of anthologies of hip hop, poetry and art and the publication Poets for Palestine. He is the author of two collections of poetry. Kanazi’s political commentary has been featured by news outlets throughout the world, including the New York Times, Salon, Al Jazeera, and BBC Radio. He is a Lannan Residency Fellow and is on the advisory board of the US Campaign for the Academic and Cultural Boycott of Israel.

Faithfully Disturbing the Peace

FOURTH SUNDAY AFTER PENTECOST

Prayer of the Day: Teach us, good Lord God, to serve you as you deserve, to give and not to count the cost, to fight and not to heed the wounds, to toil and not to seek for rest, to labor and not to ask for reward, except that of knowing that we do your will, through Jesus Crist, our Savior and Lord.

“Do not think that I have come to bring peace to the earth; I have not come to bring peace, but a sword. For I have come to set a man against his father, and a daughter against her mother, and a daughter-in-law against her mother-in-law; and one’s foes will be members of one’s own household.” Matthew 10:34-36.

Today was Juneteenth, a day that was established just last year as a federally recognized holiday by the United States Congress. Juneteenth commemorates the day on which federal troops arrived in Galveston, Texas on June 19, 1865 to take control of the state and ensure that all enslaved people be freed. Thankfully, we have reached a point at which we acknowledge publicly the dark history of slavery in our nation and the point at which it was formally terminated. Sadly, it took us over two hundred years of slavery, a century of Jim Crow, a relentless fight by Black citizens to obtain the civil liberties the rest of us take for granted, a pandemic laying bare the stark discrepancies that still exist between Black and white citizens in terms of health care, credit and land ownership and the murder of an innocent Black man by a police officer in order to get there. Truth be told, we still are not there.

Coincidentally (or not) I have been reading The 1619 Project, a book that expands upon the Sunday, August 18, 2022 New York Times special magazine bearing the same title. To make a long story short, the magazine article sought in an abbreviated way to shed light on the pivotal role played by the institution of slavery in the formation of our country, the perpetuation of white supremacy throughout the country and especially in the American south for over a century thereafter and the continuing detrimental effects of systemic racism in contemporary American society. As one might expect, the project met with sustained backlash. U.S. Senator Tom Cotton introduced a bill in the United States Senate entitled the “Saving American History Act.”[1] Similar legislation has been introduced in several Republican dominated states.[2] Suffice to say, there is a determined effort by a significant part of white America to prevent this dark aspect of our nation’s history, too frequently excluded and downplayed in our nation’s mythology surrounding its origins, from coming to light.

Coincidentally (or not), Sunday’s gospel speaks directly to our penchant for self deception and falsification, personal and collective:

“…nothing is covered up that will not be uncovered, and nothing secret that will not become known. What I say to you in the dark, tell in the light; and what you hear whispered, proclaim from the housetops.” Matthew 10:26-27.

To be a disciple of Jesus is to speak the truth, even when it disturbs the peace, even when it elicits hostility, even when it divides churches, splits families and ends friendships. Discipleship is about speaking the truth even when you feel you cannot do it articulately, even when you wish there were someone else that could speak better, even when your voice is shaking. And the truth is that systemic racism infects our educational institutions, our workplaces, our system of justice and, not least, our churches. It is a truth of which we have always been vaguely aware. But the election and presidency of Donald Trump have made unavoidably clear the breadth, depth and persistence of white supremacy and the pain it inflicts on people of color every second of every day. Indeed, that much needed clarity might be the one and only positive contribution of the Trump legacy.

Naturally, I applaud efforts such as the 1619 Project to tell the American story and the story of American Christianity[3] truthfully. But public witness only takes us so far. As Jesus noted, a prophet is without honor in the prophet’s own home and among the prophet’s own people. Yet that is precisely where the witness to truth is most needed. There are, of course, potent reasons for letting Uncle Ned’s racist remark pass without comment in the interest of not spoiling Thanksgiving dinner for everyone else. There is an argument to be made against introducing the issue of racial justice to a congregation that is struggling to sustain itself financially and is already divided and demoralized. One might question the wisdom of a denominational church body already in decline and hardly able to maintain its own ministries tithing a substantial portion of its income to support Black churches as a step toward reparations owed by American society as a whole. Given the fragility of our families, congregations and the churches of which they are a part, we might rather settle for peace at home, peace in the congregation and peace in the ecclesiastical household than the peace won through the hard work of doing justice, loving kindness and walking humbly with God. But the peace of silence comes at a terrible price, a price that is paid by victims of exclusion, intimidation and violence required to maintain it.

If it was not clear to us before, the murder of George Floyd by a Minneapolis police officer and all that followed should convince us that evil does not go away simply because we choose to ignore it. The people we witnessed storming our capital two years ago chanting racist and antisemitic slogans, displaying hangman’s nooses and flying the confederate flag of racism testify to the sickness of our culture and the pervasiveness of the lies our nation has been telling itself about itself for the last couple of centuries. The false mythology of America that we learned in school as history, a mythology that has ignored, downplayed and minimized the role of racism and the creed of white supremacy, needs to be exposed.

Unfortunately, the people who most need to hear the testimony given voice in the 1619 Project are not likely to read it. Many of them are ingesting a steady diet of right wing propaganda from the likes of Fox, One America News and Truth Social. Nevertheless, they have neighbors like you and me. They have family members like us. They use the same nail salons and barber shops we do and frequently attend the same churches. You might not change Uncle Ned’s mind at the Thanksgiving dinner table. But by calling him out on his racism, you let the rest of your family-including impressionable children-know that his bigotry is not acceptable and has no place in your home. You may not sway the loudmouth in the barbershop, but by speaking out, you might well open the minds of others standing by or encourage those who might have been fearful of speaking up.

As for preaching the truth about America’s racism to the church, what is the worst that could happen? You might lose members. You might lose your job. But while you are thinking about that, thing about this: In the sixth chapter of John’s gospel Jesus went from an adoring congregation of over five thousand to a following of twelve in a matter of days. The truth does not always win converts. Sometimes it makes enemies. Despite what our churches say on their marques about everybody being welcome, if the Proud Boys or the Oath Keepers would feel welcome and comfortable in your church, you are probably not doing your job. The good news that God’s limitless love does not recognize borders, require documentation, distinguish on the basis of humanly concocted categories of race, have any regard for class or respect for cultural measures of worth and achievement is mighty bad news for white people desperate to hang onto their societal privilege. But these are the words of eternal life. Those who do not recognize them as such are the ones who need most to hear them.

Jesus warns us not to fear human retaliation, but rather to fear God. Fear of God does not go down well in my ever white, ever polite progressive protestant tradition. But it strikes me that if we really did fear God, there would be a lot less other things to fear-such as ruining Thanksgiving dinner, creating an uncomfortable scene at the nail salon, offending one of the church’s biggest contributors or failing to be re-elected bishop. Indeed, if these are the only consequences we face for telling the truth, we should count ourselves blessed. Throughout history and to this very day many have paid and continue to pay a higher price. Jesus tells us frankly that speaking truthfully about what the rest of the world would rather ignore, deny or erase will bring us into the same struggle to which he gave his life. He reminds us, however, that all who lose themselves in that struggle will find themselves. Matthew 10:39. The truth, painful as it is, makes us free.

Here is a poem by Denise Levertov dismissing the peace which is merely tolerance of evil.

Goodbye to Tolerance

Genial poets, pink-faced

earnest wits—

you have given the world

some choice morsels,

gobbets of language presented

as one presents T-bone steak

and Cherries Jubilee.

Goodbye, goodbye,

I don’t care

if I never taste your fine food again,

neutral fellows, seers of every side.

Tolerance, what crimes

are committed in your name.

And you, good women, bakers of nicest bread,

blood donors. Your crumbs

choke me, I would not want

a drop of your blood in me, it is pumped

by weak hearts, perfect pulses that never

falter: irresponsive

to nightmare reality.

It is my brothers, my sisters,

whose blood spurts out and stops

forever

because you choose to believe it is not your business.

Goodbye, goodbye,

your poems

shut their little mouths,

your loaves grow moldy,

a gulf has split

the ground between us,

and you won’t wave, you’re looking

another way.

We shan’t meet again—

unless you leap it, leaving

behind you the cherished

worms of your dispassion,

your pallid ironies,

your jovial, murderous,

wry-humored balanced judgment,

leap over, un-

balanced? … then

how our fanatic tears

would flow and mingle

for joy …

Denise Levertov (1923–1997) never received a formal education. Nevertheless, she created a highly regarded body of poetry that earned her recognition as one of America’s most respected poets. Her father, Paul Philip Levertov, was a Russian Jew who converted to Christianity and subsequently moved to England where he became an Anglican minister. Levertov grew up in a household surrounded by books and people talking about them in many languages. During World War II, Levertov pursued nurse’s training and spent three years as a civilian nurse at several hospitals in London. Levertov came to the United States in 1948, after marrying American writer Mitchell Goodman. During the 1960s Levertov became a staunch critic of the Vietnam war, a topic addressed in many of her poems of that era. Levertov died of lymphoma at the age of seventy-four. You can read more about Denise Levertov and sample more of her poetry at the Poetry Foundation Website.

[1] This bill never became law.

[2] One interesting permutation of these measures is a relentless effort to keep “CRT” out of public schools. CRT is an acronym for Critical Race Theory, a catch all phrase for a diverse group of legal scholars whose writings explore the relationship between race, racism and power as it pertains to the evolution of American law. Though I am neither a legal scholar nor an expert on Critical Race Theory, as a law school graduate I have some familiarity with it. As with any scholarly movement, there are many diverse and sometimes conflicting voices within it. There is no one single “theory.” Moreover, anyone with the slightest understanding of what Critical Race Theory actually is and more than two brain cells to rub together has to know that it is not being taught to primary or secondary students. Thus, legislation to put an end to this non-event is rather like outlawing the keeping of unicorns within city limits.

[3] The 1619 Project includes an essay by Anthea Butler on the Black church and the critical role it has and continues to play in the struggle for freedom, equality and civil liberties that has defined African American existence in the United States. See 1619 Project, (c. 2021 by The New York Times Company) pp. 335-353. That an enslaved people were able to take the religion and Bible of their captors, liberate it from its Constantinian captivity to the instrumentality of oppression and recapture the radical message of the Exodus, the Return from Exile and the Cross and Resurrection of the Messiah for the downtrodden is one of the most remarkable facts of history.

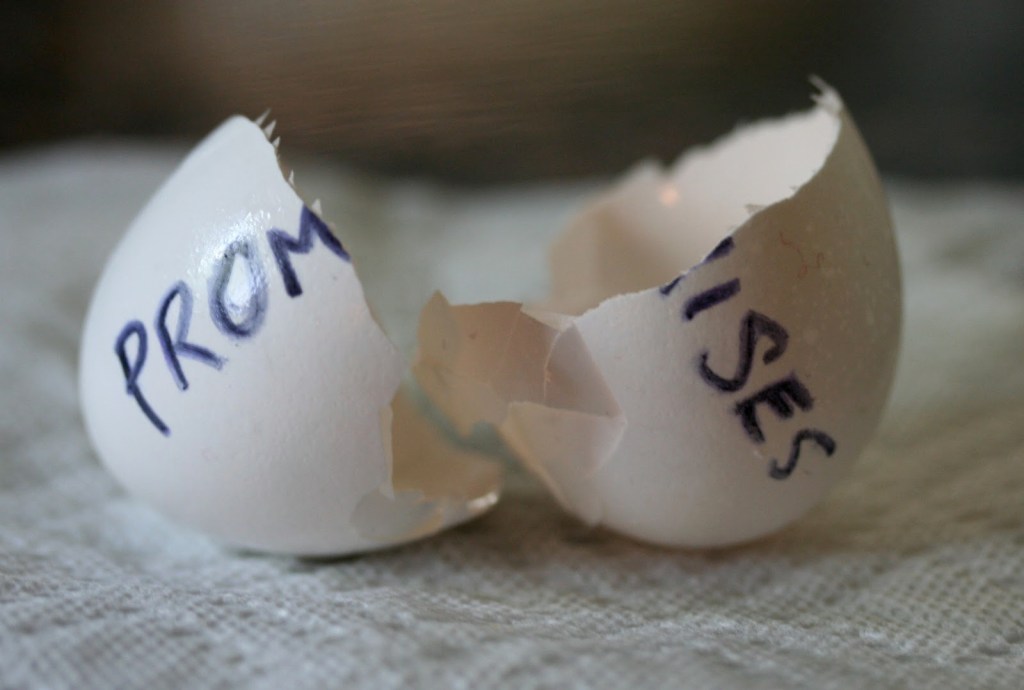

Promises, Promises

SECOND SUNDAY AFTER PENTECOST

Prayer of the Day: God of compassion, you have opened the way for us and brought us to yourself. Pour your love into our hearts, that, overflowing with joy, we may freely share the blessings of your realm and faithfully proclaim the good news of your Son, Jesus Christ, our Savior and Lord.

“So Moses came, summoned the elders of the people, and set before them all these words that the Lord had commanded him. The people all answered as one: ‘Everything that the Lord has spoken we will do.’ Moses reported the words of the people to the Lord.” Exodus 19:7-8.

We know that the people of Israel kept this promise only imperfectly-as do all of us who make big promises. No doubt the people were sincere. I have no doubt that Saint Peter was sincere when he told Jesus that he was ready to go to prison or even death with him. I have no doubt that every couple joined in marriage are perfectly sincere when they promise to “join with [one another] and share in all that is to come.” But for one reason or another, we often end up breaking the promises we make.

There are many reasons promises get broken. Sometimes it is a matter of overestimating one’s own degree of courage, strength or ability. Sometimes circumstances over which one has no control make keeping a promise impossible. Sometimes the conditions under which the promise was made change such that keeping the promise under those changed conditions would be hurtful, unethical or unjust. Sometimes a promise is made recklessly and without due consideration for the consequences that might follow to third parties. Better to renege on such a promise than follow through and cause injury or harm to unsuspecting and uninvolved persons.

Sometimes people make promises they know they cannot keep. Yours truly promised his children when they were small that he and their mother would always protect and keep them safe. Of course, I knew that I was not being entirely truthful. As much as I would have liked to think otherwise, I knew there were many things from which I was powerless to protect my children, even when they were small and always at home. Yet I continued to give them the assurance of my protection because I believed then and continue to believe that children need and deserve to feel safe, secure and free from danger. I figured that, should the unthinkable happen, should one of my children be traumatized in some way despite my best protective efforts, I would simply have to cross that bridge when, God forbid, I came to it. You might call this promise an act of faith. I knew I might not be able to keep it, but trusted nonetheless that God would be present either to do what I was unable to do or help me pick up the pieces of a shattered promise I failed keep.

This last Sunday our congregation confirmed its one confirmand, a remarkably mature and articulate thirteen-year-old whose moving statement of faith left us in awe. During the rite of confirmation, the confirmand is asked to affirm her baptismal vow “to trust God, proclaim Christ through word and deed, care for others and the world God made, and work for justice and peace.” That promise is every bit as weighty as the Israelites’ commitment to fulfill all the commandments delivered to them by Moses. It is also a promise the church manages to keep about as well as Israel was able to keep the commandments. For that reason, the response to the inquiry is: “I do, and I ask God to help me.” We know all too well that the promises we make are too big for us to keep on our own. We know that we have no idea what keeping our baptismal vow will require of us, whether we will have the courage and stamina to remain faithful in times of trial or how we will manage to go on in the face of failure, tragedy and trauma. In all those circumstances, however, we cling to the promise that God will be there for us.

I think perhaps that is what I meant when I promised to protect my children. I might not be able to keep them from getting hurt, getting their hearts broken or making bad decisions. But I can be there for them. I can love them. Love takes shape in different ways under different circumstances. Sometimes love is tender, supportive and gentle. Sometimes love must be tough. Sometimes love intervenes to change a dangerous life trajectory. Sometimes love must take a step back and let events take their course. Always love forgives. Always love leaves the door open. Always love persists.

God’s promise is that God will never stop loving the world God made and the people for whom God bled and died. God’s love is sometimes like being in “God’s bosom safely gathered.” It sometimes takes the shape of judgment and rebuke. But whether in grace or judgment, God is always there “for” us-never against. God will always be there to forgive and help us put back together the broken pieces of our failed promises. Unlike our promises, God’s are unbreakable. As our Psalm for Sunday reminds us,

“For the Lord is good;

his steadfast love endures for ever,

and his faithfulness to all generations.” Psalm 100:5.

So we are bold to affirm again and again the promises made in our baptismal vows. We continue to make promises to one another. After all, our human communities are held together by promises and our confident hope in their fulfilment. Beyond that, all creation is held together by the God whose faithfulness to God’s promises never fails.

Here is a poem about faithfulness by Emma Lazarus.

Rosh-Hashanah, 5643

Not while the snow-shroud round dead earth is rolled,

And naked branches point to frozen skies.—

When orchards burn their lamps of fiery gold,

The grape glows like a jewel, and the corn

A sea of beauty and abundance lies,

Then the new year is born.

Look where the mother of the months uplifts

In the green clearness of the unsunned West,

Her ivory horn of plenty, dropping gifts,

Cool, harvest-feeding dews, fine-winnowed light;

Tired labor with fruition, joy and rest

Profusely to requite.

Blow, Israel, the sacred cornet! Call

Back to thy courts whatever faint heart throb

With thine ancestral blood, thy need craves all.

The red, dark year is dead, the year just born

Leads on from anguish wrought by priest and mob,

To what undreamed-of morn?

For never yet, since on the holy height,

The Temple’s marble walls of white and green

Carved like the sea-waves, fell, and the world’s light

Went out in darkness,—never was the year

Greater with portent and with promise seen,

Than this eve now and here.

Even as the Prophet promised, so your tent

Hath been enlarged unto earth’s farthest rim.

To snow-capped Sierras from vast steppes ye went,

Through fire and blood and tempest-tossing wave,

For freedom to proclaim and worship Him,

Mighty to slay and save.

High above flood and fire ye held the scroll,

Out of the depths ye published still the Word.

No bodily pang had power to swerve your soul:

Ye, in a cynic age of crumbling faiths,

Lived to bear witness to the living Lord,

Or died a thousand deaths.

In two divided streams the exiles part,

One rolling homeward to its ancient source,

One rushing sunward with fresh will, new heart.

By each the truth is spread, the law unfurled,

Each separate soul contains the nation’s force,

And both embrace the world.

Kindle the silver candle’s seven rays,

Offer the first fruits of the clustered bowers,

The garnered spoil of bees. With prayer and praise

Rejoice that once more tried, once more we prove

How strength of supreme suffering still is ours

For Truth and Law and Love.

Source: Emma Lazarus: Selected Poems and Other Writings (c. Broadview Press 2002)

Emma Lazarus (1849-1887) is most famous for the words inscribed on the Statute of Liberty from her poem, The New Colossus:

“Give me your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,

The wretched refuse of your teeming shore.

Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me,

I lift my lamp beside the golden door!”

Lazarus was one of the first successful and publically recognized Jewish American authors. She was born in New York City to a wealthy family. She began writing and translating poetry as a teenager and was publishing translations of German poems by the 1860s. Lazarus was moved by the fierce persecution of her people in Russia, a frequent topic of her writings, as well as their struggles to assimilate into American culture. You can sample more of Emma Lazarus’ poetry and read more about her at the Poetry Foundation website.

Discipling the Nations

HOLY TRINITY

Prayer of the Day: Almighty Creator and ever-living God: we worship your glory, eternal Three-in-One, and we praise your power, majestic One-in-Three. Keep us steadfast in this faith, defend us in all adversity, and bring us at last into your presence, where you live in endless joy and love, Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, one God, now and forever.

“Go therefore and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, and teaching them to obey everything that I have commanded you.” Matthew 28:19-20.

The American author, Samuel Clemens (aka Mark Twain) once said that “to be good is noble. To teach another to be good is more noble still-and a lot less trouble.” I think of that quote often when I read the bold social justice proclamations by churches like my own. It is all well and good for the church to speak truth to power, to expose, challenge and call for the eradication of systemic racism in government, education and commerce. But when it comes from a church that has been and still is overwhelmingly white, has benefited historically and continues to benefit from white privilege and whose ecclesiastical wealth far exceeds that of most Black churches with which we claim to united-it tends to lack credibility. The cruel, unjust and heartless society we purport to condemn might well throw our own Bible back in our faces with the admonition to “remove the log” from our own eye before attempting to open theirs. Matthew 7:1-5.

In Sunday’s gospel, Jesus utters what we have come to call “the great commission.” He sends his disciples out to “make disciples of all nations.” Well, no he doesn’t. The English translation, “make disciples,” does not capture the meaning conveyed in the original Greek text. Jesus is not commanding his disciples to make the nations into something called disciples. In the Greek, there is no noun, “disciple.” Instead, “disciple” is the verb, the engine of the sentence. Thus, the command is to “disciple all nations.” It involves “teaching them to obey everything” that Jesus has commanded. That is done as much by preaching as example. “Let your light so shine among others that they see your good works and glorify your Father in heaven.” Matthew 5:16. Witness to the nations comes from the heart of a community formed by the Sermon on the Mount. One might call this a community that “practices what it preaches.” But I prefer to say that it is a community whose preaching flows from its faithful practices.

The implication is clear. You have to be a disciple in order to make one. The original disciples became such by following Jesus and the way is no different for us. Churches are to be furnaces in which disciples are formed for witness and service. Our American churches, however, have undergone some formation of their own in a context that makes discipling difficult. Most of us do not view our churches as families into which we are born through baptism. We tend to view them as voluntary organizations of which we are willing members. It is all transactional. I join the church of my choice and receive certain benefits and privileges in return. These include a place to be married and buried; a place to baptize and confirm my kids, a place that offers me some socialization and entertainment. If my church does not give me everything to which I believe I am entitled, or another church down the road offers better preaching, better hymns or better programs, I am out the door. Why should I stay at a church that does not speak to me, that does not meet my needs or comport with my expectations? In accord with our capitalist instincts, we Americans build churches designed to market religious commodities rather than calling people to become fishers for people. Accordingly, our churches produce consumers rather than making disciples. So the question is, how can our churches better become and be disciples of Jesus in our contemporary setting?

I have two thoughts. First, we can become truly diverse. That is particularly important in a society built on a foundation of systemic racism and permeated with hateful ideologies grounded in white supremacy. The rise of Donald Trump and his capture of the Republican party has laid bare the extent and depth of racial hate in our land. The murder of George Floyd and the scandalous disparity in access to medical care and other services between whites and non white citizens have made plain the terrible cost the centuries of racial injustice impose. Diversity is not some trendy new byword. It is at the heart of the good news we proclaim. From its inception, the gospel has been proclaimed as a good word for “the nations” and the church has been understood as made up of “all nations, tribes and tongues.” Never has the need to proclaim in word and deed the common humanity of all people and God’s love for all people been more urgent.

In one sense, we already are diverse. Christians in the United States are heavily represented by almost every ethnicity. Sadly, however, we are divided by denominational loyalties often reflecting the same racial/ethnic fault lines plaguing society as a whole. We tend to seek out and welcome our own kind. We mainliners have been aware of that for decades and have been trying to remedy the malady through intentional outreach to people of color, aggressive recruiting of minority persons for ministry and formulae for ensuring that a certain percentage of our elected leaders are non-white. Yet as well intentioned as these efforts are, they do not address the systemic societal framework of racial discrimination that determines where we live, where we go to school, who we meet, with whom we socialize, what career opportunities are open to us and, yes, where we go to church. Trying to remedy racism by integrating the church is rather like trying to end air pollution by changing your furnace filter.

Yet I believe there is a way out of our ethnic captivity. If we are prepared to acknowledge that the church is a single body as Saint Paul teaches us; if we acknowledge that when one part of the body is injured, the whole body suffers; if we follow Saint Paul’s example in urging his gentile churches to contribute out of their abundance to meet the need of the famine stricken churches of Judea; then it seems to me clear how the wealthier mainline churches, like my own, should respond to the Black churches and missions that are struggling on the front lines against racism and economic injustice. The wealth our national church, synods and congregations have tied up in real estate, sitting in endowments and planted in banks can fuel the fight for racial justice and equity while providing a powerful witness to what the reign of God looks like. I suggested one step in that direction in my “Open Letter to the ELCA Presiding Bishop and Synodical Bishops: A Modest Proposal for Reparational Tithe.” Such action will not desegregate our churches overnight. But it will send a clear message that we mean what we said in our “Declaration Of The ELCA To People Of African Descent.”

I am convinced that remedying the systemic injustice that has and continues to oppress people of color in general and African Americans in particular will require an effort on the level of the New Deal or the Marshall Plan. There is currently little appetite for any such effort in American government and I doubt more screechy preachy church social statements calling for it will alter that disinterest. So perhaps it is time we started to be the change we keep calling for. Maybe it is time for bishops and church leaders to stop acting like CEOs of failing corporations answering to their shareholders, put on their grownup pants and start challenging their churches with concrete proposals for doing with our own assets what we are calling our representatives to do with their constituents’ tax dollars. In the Book of Acts, it was the example of the disciples’ acts of mercy and their selfless lifestyle as much as their preaching that won the hearts of so many to the New Testament church. Who can tell whether the corporate example of a church doing justice within itself will influence the larger society to do likewise?

My second thought is global. As I write this article, Orthodox Christians are daily killing each other by the hundreds in eastern Europe in the bloodiest European conflict since World War II. This is but the most obvious example of an idolatry infecting the church throughout the world. The fact that we are prepared to engage in lethal conflicts pitting Christian against Christian shows that our loyalty to the gods of blood, race, nation and soil takes precedence over out baptismal vows to love our neighbors, near and far, as ourselves. The frightening rise of nationalist/populist movements worldwide has been well documented by the Lutheran World Federation’s study, Resisting Exclusion: Global Theological Responses to Populism, (pub. by Evangelische Verlangsanstalt GmbH, Leipzig, Germany, under the auspices of The Lutheran World Federation). Never has it been more important for the church to assert its catholicity, its claim that ultimate loyalty belongs to Jesus and the reign of God he proclaims and that no nation, government or other human authority must take precedence over the great commandments to love God above all else and to love one’s neighbor as oneself. In a world on the edge of disintegration and global war, the church is called to be the visible sign of Christ’s Body, the Incarnate Word that holds creation together against all the hateful ideologies, nationalistic ambitions and ancient blood feuds threatening to rip it apart.

We need a new ecumenical movement to build a united global church. I understand how difficult that would be and that ecumenism has failed in the past to produce meaningful unity. But I think that is in large part due to our fixation on differences in doctrine and practice. Let me be clear. I believe doctrine is important. I believe discussions about worship, the sacraments, our creeds and ethical concerns are important and worth having. But should they be allowed to get in the way of our common basic assertion that the human family is one and that through the lens of Jesus’ life, death and resurrection there can be no hierarchy of value when it comes to the worth of human lives? And can we credibly make that assertion when our national loyalties trump our loyalty to Jesus and his gentle reign? Do we stand a chance of discipling the nations when we will not disciple ourselves? Can we teach the nations to observe all that Jesus commanded when we ourselves have no intention of following those commands?

I know that these two thoughts of mine are not new, that smarter people than me have articulated them with greater clarity, that better people than me have struggled to bring them to fruition and that the prospects of their taking root now are no greater than in the past. But I can’t help thinking that, perhaps, if enough of us begin loving Jesus and the reign of God he lived and died for more than our institutions, more than our sanctuaries, more than our comfortable traditions, more than our countries, more than life itself-God’s Spirit might once gain make use of us to “turn the world upside down.” See Acts 17:6.

Here is a poem by Denise Levertov about the kind of peacemaking that resembles the discipling I believe our gospel lesson is talking about.

Making Peace

A voice from the dark called out,

‘The poets must give us

imagination of peace, to oust the intense, familiar

imagination of disaster. Peace, not only

the absence of war.’

But peace, like a poem,

is not there ahead of itself,

can’t be imagined before it is made,

can’t be known except

in the words of its making,

grammar of justice,

syntax of mutual aid.

A feeling towards it,

dimly sensing a rhythm, is all we have

until we begin to utter its metaphors,

learning them as we speak.

A line of peace might appear

if we restructured the sentence our lives are making,

revoked its reaffirmation of profit and power,

questioned our needs, allowed

long pauses . . .

A cadence of peace might balance its weight

on that different fulcrum; peace, a presence,

an energy field more intense than war,

might pulse then,

stanza by stanza into the world,

each act of living

one of its words, each word

a vibration of light—facets

of the forming crystal.

Source: Breathing the Water (New Directions Publishing Corporation, 1987) Denise Levertov (1923–1997) never received a formal education. Nevertheless, she created a highly regarded body of poetry that earned her recognition as one of America’s most respected poets. Her father, Paul Philip Levertov, was a Russian Jew who converted to Christianity and subsequently moved to England where he became an Anglican minister. Levertov grew up in a household surrounded by books and people talking about them in many languages. During World War II, Levertov pursued nurse’s training and spent three years as a civilian nurse at several hospitals in London. Levertov came to the United States in 1948, after marrying American writer Mitchell Goodman. During the 1960s Levertov became a staunch critic of the Vietnam war, a topic addressed in many of her poems of that era. Levertov died of lymphoma at the age of seventy-four. You can read more about Denise Levertov and sample more of her poetry at the Poetry Foundation Website.