Monthly Archives: March 2019

The Other Prodigal Son

FOURTH SUNDAY IN LENT

FOURTH SUNDAY IN LENT

Joshua 5:9-12

Psalm 32

2 Corinthians 5:16-21

Luke 15:1-3, 11b-32

Prayer of the Day: God of compassion, you welcome the wayward, and you embrace us all with your mercy. By our baptism clothe us with garments of your grace, and feed us at the table of your love, through Jesus Christ, our Savior and Lord, who lives and reigns with you and the Holy Spirit, one God, now and forever.

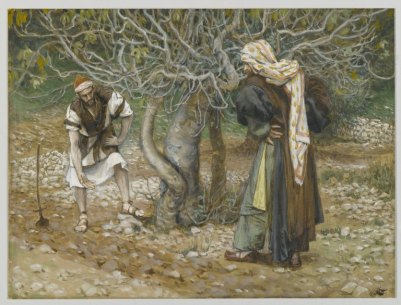

The Prodigal Son is one of those biblical stories that is so well known that it rings a bell even for the most thoroughly secularized mind. The assurance that our God welcomes back those of us whose bad decisions have led us into self-destructive ways and put us in a bad place is good news. We can’t hear that message often enough. Nevertheless, truth be told, the text has become slightly shopworn for those of us who have been preaching for decades. I always find myself struggling to tell this story in fresh and creative ways.

One approach I have taken is to read the parable through the eyes of the elder son. After all, most of us church people are probably more like him than the prodigal. We are the ones who contribute the money, volunteer the time and do the work that ensures the church will be there on Christmas Eve and Easter Sunday for those who come waltzing in on those days only. Though I expect we all have a few things in our past we regret, few of us have reached the level of ruin at which the younger son in the parable found himself. Most of us church people have led relatively respectable lives despite our shortcomings. Therefore, it is worth asking ourselves: How would I feel if I were the elder son in this story? In order to help my congregation find themselves in this place, I preached the following sermon taking the form of two letters: one from the elder son to his father and the other being the father’s reply.

Dear Dad:

Since we had words yesterday, I figured it might be a good idea to take a deep breath, sit down and think a bit. I did that. Now I want to put into writing exactly how I feel about what happened between us.

Dad, you have to admit that I’ve been a good son to you. You never had to wonder where I was late at night. If I wasn’t in bed, I was out in the shop working on fixing a plow so it would be ready to go at the crack of dawn, or tending one of our cows giving birth or investigating what I thought might have been fox or a weasel sneaking into the chicken coop. During the day, I was working side by side with you under the noon day sun. When the river busted its banks and threatened to wipe out our entire wheat crop last spring, I was right there with you and the hired hands piling up sandbags until I could hardly stand. If you will recall, that other son of yours was at home sleeping off one of his many drinking binges. How many times did you have to go down to the police station or municipal court to bail that kid out of some sort of trouble? How many times did he come home so drunk he couldn’t find the front door? I’m afraid I’ve lost count.

See, here’s the thing Dad. It’s always been about him. You were always fretting about your beloved younger son: “What’s wrong with the poor boy? Why does he seem so angry? Why is he always getting into trouble?” Don’t think I haven’t noticed the tears you tried so hard to hide from the rest of us, the tears you shed for him. Well guess what, Dad. You have two sons. I guess because I never made any trouble for you, you never bothered to notice me. You never stopped to think about what might be bothering me. Yes, growing up was tough for me, too. Yet it always seemed you treated me as though I wasn’t even there. But I want to tell you Dad that I am here. I’ve always been here. I have been pouring my blood, sweat and tears into this little farm from the time I could pick up a tool. But I never heard you say, “Thanks son,” or “Good job son,” or “Why don’t you take the evening off and have a good time with your buddies-on me.” No sir! Not a single word. Not a single slap on the back.

I was hoping, praying that once that son of yours took his share of the estate and left, maybe, just maybe you would notice me and appreciate me. But no, all you did was worry and fret over that self-centered brat. You never even looked my way! You just kept your eye on the road waiting for him to come back. And sure enough, when that son of yours comes back, filthy, ragged and smelling like a pig, you can’t run fast enough to embrace him, shower him with tears, give him a new robe and-here’s the biggest slap in the face of all-you kill for him the fatted calf and throw a big party. And you wonder why I am upset? You wonder why I don’t want to join the celebration? That son of yours has given you nothing but grief, but you kill for him the fatted calf. I have given you nothing but obedience and respect, but you haven’t given me a lousy goat. Go figure.

Your son.

Dear Son:

I have read with interest your letter to me. And I have to admit, you are right about a couple of things. First off, it’s true that I never thanked you for doing your chores and behaving yourself. But I don’t recall your ever thanking me and your mother for the three meals a day you have gotten for all of your life, the cloths on your back or the roof you sleep under every night. And that’s OK. I don’t expect any thanks for that. It’s what a father owes his son-just as a son owes his father obedience and respect. No thanks due in either direction as I see it. Furthermore, as I told you yesterday, everything I have is yours. Your brother squandered his share of the inheritance and that’s gone. You are next in line to get the farm so I haven’t given to your brother anything that rightfully belongs to you.

But I have given you a lot more than just this farm. As you point out, we have spent the better part of our lives together working side by side. Don’t you remember all those afternoons we sat exhausted in the shade of the elm trees at the edge of the field sharing our lunch, swapping jokes with the hired hands and singing those old songs of Zion together? Your brother missed out on all of that. Remember the sense of satisfaction we felt every year at harvest time when we loaded sack after sack of grain on the ox cart, how we marveled at that ageless miracle of the full grain coming from those tiny seeds we planted with such care and watched over like worried mother hens? Your brother will never know that joy either. What I am trying to tell you, son, is that there is no reward for loyalty, devotion and hard work. These things are their own reward. It’s like I told you yesterday. You are always with me and everything I have is yours. We’ve shared our lives together. What more can a father give to his son?

You are also right about something else. I love your brother-yes, your brother, the one you keep referring to as “that son of yours.” I love him. But what is that to you? Do you think love is a finite quantity like land or cattle or money? Do you think love is something limited, so that if I spare any love on your brother there is less for you? No, my son. You can overspend your bank account. You can over mortgage your land and lose it. But you can never exhaust the reservoir of love for the people around you. In fact, here’s the mystery about love: the more people you love and the more deeply you love them, the more love you have share. And that’s because the source of love is not in your own heart, but in the heart of God, our heavenly Father. Because God loves us all so much, we have a bottomless well of love to draw on for each other.

You think my love is wasted on your brother. But that’s because you have somehow gotten the notion that love is a reward for obedience, for good behavior or great accomplishments. Your problem, son, is not that you are unloved. Your problem is that you have no idea how deeply loved you really are. You have been trying so hard all your life to earn my love that you never allowed me simply to give it to you. Your brother may have wasted his father’s money, but you have been wasting your father’s love. Now you tell me, which do you think is the greater loss? Who is really the prodigal one here? Make no mistake about it. You are a good kid, you work hard and that makes life easier for both of us. But that isn’t why I love you. I love you because you are my son and that is what fathers do. I’d love you just as much if you were as reckless and irresponsible as that knuckle head brother of yours.

That brings me to my final point. Just as I embraced your brother and welcomed him home, so now you need to do the same. No, he doesn’t deserve it. But I hope by now I have convinced you that love has nothing to do with deserving. Your brother did not deserve the party I gave him. But he needed it. He needed to be shown that, as much as his actions may have hurt and disappointed me, he is still my son and this is still his home. And you need to learn that, as faithful and obedient as you have been all these years, I love you not for that reason but because you are my boy. Son, as I told you before, I have given you all that I am and all that I have. Now nothing could make this old father happier than to see his two sons embrace. With my deepest love,

Your Dad.

May the peace of God which passes all understanding so reconcile us. Amen.

Here’s another take on the Prodigal Son by poet Affa Michael Weaver.

Washing the Car with My Father

Mishaps, Massacres and Mercy

Isaiah 55:1-9

Psalm 63:1-8

1 Corinthians 10:1-13

Luke 13:1-9

Prayer of the Day: Eternal God, your kingdom has broken into our troubled world through the life, death, and resurrection of your Son. Help us to hear your word and obey it, and bring your saving love to fruition in our lives, through Jesus Christ, our Savior and Lord, who lives and reigns with you and the Holy Spirit, one God, now and forever.

Young lives tragically and undeservedly cut short. A life mercifully and undeservedly spared. This Sunday’s gospel places these very different outcomes in stark contrast. The story about the eighteen people killed in the collapse of a tower and the Galileans killed in the very act of worship both have a contemporary ring to them. This week an Ethiopian passenger jet plunged to earth killing all on board. Then we got the news of the forty-nine men, women and children shot to death while worshiping in their mosques. Why these people? Why now? It is not clear why Pilate killed the Galileans in our reading. It is possible they were involved in an insurrection of some sort, but they could also have been innocent victims selected for slaughter at random “to send a message” to any would be insurrectionists. Maybe, like so many killed in Syria and Sudan these days, they were simply caught in the crossfire of someone else’s fight. Violence against innocent civilians is distressingly common place in our world.

Such events send chills down the spine. They bring home to us how frail and vulnerable we all are. It takes only one defective screw, a second’s inattention at the wheel, an unanticipated change in weather patterns to cut off a bright and promising future for an unsuspecting victim. It takes years of dedication, patience, sacrifice and anguish to raise a child. It takes only the pull of a trigger to erase all of that in an instant. When we read about these horrific events, we can’t help thinking, “That could have been me or someone I love!”

Blaming the victims of misfortune comes naturally. We take a perverse comfort in believing that victims of accidents and violence were somehow at fault for what befell them. “He should have known better than to hike that trail this time of year.” “She shouldn’t have gone to that party dressed so provocatively.” “They should never have traveled to a dangerous country like that.” After all, if I can identify some error, moral infraction or misjudgment on the part of the victims, it is easier for me to convince myself that I can avoid their fate. I just have to exercise more care than they did or refrain from the careless and irresponsible behavior I believe led to their cruel end. I can fool myself into thinking that I am in control of my life and safe from the randomness with which death and destruction so often strike.

Jesus dispels that notion altogether. Are the victims of accident and violence any more deserving of death than those who lived to tell about it? “I tell you, No,” says Jesus, but he goes on to say that “unless you repent you will all likewise perish.” What does Jesus mean by that? I doubt he meant that repentance shields one from a violent death. Jesus has already made it clear that repentance and faith take us on the path of the cross. Discipleship makes a violent end more rather than less likely. I believe the explanation lies hidden in Jesus’ parable of the fig tree that follows.

Unlike the seemingly hapless victims in the daily news-both in Jesus’ day and our own-the fig tree has earned the judgment of destruction passed by the owner of the vineyard. In a semi-arid climate where cultivatable land is limited, it is difficult to justify allowing an unproductive tree to go on using up valuable soil. Yet unexpected and cruel as was the fate of the victims we read about earlier, equally unexpected and undeserved is the vinedresser’s plea for mercy sparing the fig tree. It is tempting to interpret this parable allegorically with God being the owner of the vineyard and Jesus the vinedresser interceding on our behalf for mercy. But that does not work for a number of reasons. God clearly does not wish for the destruction of anyone. Even when God threatens judgment, it is with the hope that those who are so threatened will turn and repent. The owner of the vineyard is not making a threat. He has made up his mind to have the tree down. He seems to have no hope for the tree. There is no righteous indignation here. This is simply a business decision. The tree is an investment that has failed for three years to yield a return. It is time to pull the plug and invest elsewhere. The vinedresser’s motives are unclear. Perhaps he sees more potential in the tree than does the owner. In any event, the vinedresser is convinced he can get fruit out of the tree and tries to convince the owner to give him one more year.

At this point, the parable of the fig tree comes to an abrupt end leaving a lot of loose ends for us to consider. We would like to think that the owner said, “Fine. You think you can make this tree produce some figs? You have one more year. Knock yourself out.” But Jesus does not tell us so much. It is just as likely that the owner said, “You have to be kidding! For three years this tree has produced nothing. What do you think will be different about year four? Cut it down!” The parable therefor leaves us in a tenuous place. We can only conclude that we have but the present moment. Today we are alive. There is no guaranty beyond that. Yet we are to understand that the present minute is nonetheless a precious gift. We dare not allow it to languish under the illusion that there will always be more time. The tragedy of the lives lost under the fallen tower, under Pilate’s sword, in the crash of the Ethiopian jetliner and in the New Zealand mosque shootings is not merely that they were prematurely taken. The greater tragedy is our tendency to construe them as somehow the fault of the victims, something that happens to somebody else rather than recognizing in them a sobering reminder of our connection to all humanity in our frailty and vulnerability, God’s undeserved gift to us of yet another day and a call for us to use that day responding to these tragedies with the same compassion God so richly, lavishly and undeservedly pours out upon us.

Given that, undeservedly and inexplicably, we have been freely given this day, this hour, this minute-what are we going to do about it? It is tempting to begin promising to fill up our remaining days with good intentions. I will buy only Free Trade coffee; I will increase my giving to the church and to the poor; I will be more “intentional” (whatever that means) in working for justice and equality. All of those objectives are noble, but they amount to little more than New Year’s resolutions for a year we might not actually have. True discipleship begins with being rather than doing. Only a good tree is capable of bearing good fruit. Thus, before we can begin to do anything fruitful, we must be the kind of tree Jesus is looking for. We must be creatures capable of living joyfully, thankfully and obediently within the limits of our human mortality. Disciples of Jesus are called to embrace with thanksgiving life in all of its immediacy and contingency. They are challenged to receive each day as one that the Lord has made and offers as a gift. They are mindful that the number of such days is finite, that tomorrow is not a foregone conclusion and that health, strength and length of days is guaranteed to no one. But that only makes today with all of its potential and possibilities the more precious. It is out of such faithful gratitude that generosity flows. Generosity gives birth to compassion and compassion fuels zeal for justice, righteousness and reconciliation.

Here is a poem by New Hampshire poet laureate, Jane Kenyon, a woman whose struggle with depression and chronic illness taught her the art of living thankfully, generously and compassionately.

Otherwise

I got out of bed

on two strong legs.

It might have been

otherwise. I ate

cereal, sweet

milk, ripe, flawless

peach. It might

have been otherwise.

I took the dog uphill

to the birch wood.

All morning I did

the work I love.

At noon I lay down

with my mate. It might

have been otherwise.

We ate dinner together

at a table with silver

candlesticks. It might

have been otherwise.

I slept in a bed

in a room with paintings

on the walls, and

planned another day

just like this day.

But one day, I know,

it will be otherwise.

Source: Constance, Graywolf Press, 1993 (c. Jane Kenyon). Jane Kenyon was born in Ann Arbor, Michigan. She attended the University of Michigan in her hometown and completed her master’s degree there in 1972. It was there also that she met her husband, the poet Donald Hall, who taught there. Kenyon moved with Hall to Eagle Pond Farm, in New Hampshire where she lived until her untimely death in 1995 at age 47. You can read more of Jane Kenyon’s poetry and find out more about her at the Poetry Foundation Website.

Of Foxes and Hens

SECOND SUNDAY IN LENT

SECOND SUNDAY IN LENT

Genesis 15:1-12, 17-18

Psalm 27

Philippians 3:17-4:1

Luke 13:31-35

Prayer of the Day: God of the covenant, in the mystery of the cross you promise everlasting life to the world. Gather all peoples into your arms, and shelter us with your mercy, that we may rejoice in the life we share in your Son, Jesus Christ, our Savior and Lord, who lives and reigns with you and the Holy Spirit, one God, now and forever.

“O Jerusalem, Jerusalem, killing the prophets and stoning those who are sent to you! How often I would have gathered your children together as a hen gathers her brood under her wings, but you would not!” Luke 13:34.

The person that comes to mind here is Victoria Soto. If the name rings a bell, it should. Victoria was the twenty-seven-year old school teacher at Sandy Hook Elementary School killed while trying to shield her students from gunshots fired by school shooter Adam Lanza in that horrible massacre of children almost seven years ago. The image of an unarmed woman trained only in the art of teaching, nurturing and caring for children confronted by a man bent on the destruction of life and armed with an AR-15 assault rifle designed specifically for only that purpose isn’t all that different from the image of a nurturing mother hen confronted by the fox, trying to gather her panicked chicks under her wings as the predator closes in.

This is not an altogether comforting image of divine protection. Perhaps that is why the people of Jerusalem are less than enthusiastic about taking shelter with Jesus. Even if the hen could gather her chicks together under her wings, what then? The hen is no match for the fox. So, too, Jesus hardly seems a match for Herod and the empire he represents. It is not hard to understand why the people would prefer to seek protection under Herod. Tyrant, bully and amoral scoundrel that he was, Herod had the wherewithal to impose some degree of order and predictability over a people feeling vulnerable and threatened. When people are afraid, they will sacrifice their freedom, their integrity and a large measure of their wealth in exchange for a promise of security. They won’t look very carefully at the one making the promises either. Any port in a storm. But disciples of Jesus understand that the shelter he promises has nothing to do with being safe and secure. To the contrary, we have been warned that following Jesus requires daily taking up the cross, daily exposing oneself to the enemies of God’s gentle reign, daily joining him in placing his body between the weak and vulnerable on the one hand and the fox on the other.

That brings us to the bizarre story from our Genesis lesson in which Abraham slices all the animals in two. What’s that about? Why would a man take a bunch of animals, cut them in half and make a path through the two halves of each of the bloody carcasses? In order to answer this question, we need to travel back in history to the Bronze Age. Stepping out of our time capsule, we discover that mid-eastern society is made up of city states that owe their allegiance to larger kingdoms that, in time, will become the empires of the Iron Age. Obviously, such alliances were not agreements between equals. The ruler of a smaller state received a promise of non-aggression from the larger kingdom in return for payment of tribute and a pledge of military support if required. If this sounds rather like a protection racket, it is because that is essentially what these agreements were. Such lopsided alliances were sealed by covenant ceremonies in which numerous animals were slain and cut in two. The subject king would then swear absolute allegiance to the dominant king. The dominant king would then force the subject king to walk on the bloody path between the severed animal parts. This exercise was designed to produce the same effect as the horse head next to which Jack Woltz woke up in the movie, The Godfather. “See these hacked up animals little king? This is what happens to little kings that try to cross the Big King? Any questions?”

In Sunday’s lesson, God stands the whole notion of covenant making on its head. Abraham asked God “how am I to know that I shall possess [the land of Canaan]?” God’s response is to make a covenant with Abraham. Usually, it is the weaker, vassal king who seeks covenant protection from the dominant king. But here God is the one seeking a covenant with Abraham. In near eastern politics, the weaker king is the one who makes all the promises. In this case, God is the one who makes an oath to Abraham. Instead of forcing Abraham to walk between the mangled carcasses, God passes along the bloody path saying, in effect, “Abraham, if I fail to keep my promise to give you a child, a land and a blessing, may I be hacked in pieces like these animals.”

This remarkable story illustrates what one of my seminary professors, Fred Gaiser, once said: “The Old Testament tends toward incarnation.” The New Testament witness is that the Word of God became flesh, that is, God becoming vulnerable to the rending and slaughter experienced by sacrificial animals used in the covenant ceremony. In fact, we can go further and say that God’s flesh was torn apart, that God’s heart was broken and that this rending of God’s flesh was the cost of God’s faithfulness to the covenant. So understood, it is possible to recognize the cross in this strange and wonderful tale from the dawn of history.

To save us from ourselves, it takes a love that is stronger than our determination to run away from it. It requires love that is too deep ever to be revolted by our sin. This is love that is stronger than death-what St. Paul calls the “weakness of God” that is mightier than everything we think of as strength. I Corinthians 1:25. It is the only force strong enough to hold the cosmos together against the forces trying to rip it apart. That is why, to those who tell me we need bullet proof glass, metal detectors and more armed guards in our schools to make our children safe, I say no. What we need are more teachers like Victoria Soto who love our children enough to place their own lives between them and all that would harm them. We need more disciples of Jesus who love this world as much as Jesus did and are prepared to lay down their lives for its people. We need more churches that are ready to put their finances, their property and their own personal safety on the line to stand with Jesus against the foxes of this world that know only one kind of power-the power to control, manipulate and destroy life. We need love that is prepared to die on a cross-because that’s the only thing that is going to make guns, prisons, armies, locks and border walls totally obsolete.

Here is a poem by Francis Ellen Watkins Harper graphically illustrating the fierce passion of love pitted against raw power. It reminds us that the power of God is manifested chiefly at the margins of society where cruelty, injustice and terror appear to have the upper hand. It is the foolishness and weakness of the cross that leads us to confess this seemingly helpless love as the greater power.

The Slave Mother

Heard you that shriek? It rose

So wildly on the air,

It seem’d as if a burden’d heart

Was breaking in despair.

Saw you those hands so sadly clasped—

The bowed and feeble head—

The shuddering of that fragile form—

That look of grief and dread?

Saw you the sad, imploring eye?

Its every glance was pain,

As if a storm of agony

Were sweeping through the brain.

She is a mother pale with fear,

Her boy clings to her side,

And in her kyrtle vainly tries

His trembling form to hide.

He is not hers, although she bore

For him a mother’s pains;

He is not hers, although her blood

Is coursing through his veins!

He is not hers, for cruel hands

May rudely tear apart

The only wreath of household love

That binds her breaking heart.

His love has been a joyous light

That o’er her pathway smiled,

A fountain gushing ever new,

Amid life’s desert wild.

His lightest word has been a tone

Of music round her heart,

Their lives a streamlet blent in one—

Oh, Father! must they part?

They tear him from her circling arms,

Her last and fond embrace.

Oh! never more may her sad eyes

Gaze on his mournful face.

No marvel, then, these bitter shrieks

Disturb the listening air:

She is a mother, and her heart

Is breaking in despair.

Source: American Poetry: The Nineteenth Century (The Library of America, 1993). Francis Ellen Watkins Harper (1825 –1911) was an African-American abolitionist, suffragist, poet, teacher, public speaker, and writer. She was active in social reform and was a member of the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union. She published her first book of poetry at the age of 20, making her one of the first African-American published writers. In 1851 she worked with the Pennsylvania Abolition Society helping escaped slaves along the Underground Railroad on their way to Canada. You can read more about Francis Ellen Watkins Harper and sample more of her poetry at the Poetry Foundation website.

Fasting, Sex and Lent

FIRST SUNDAY IN LENT

FIRST SUNDAY IN LENT

Deuteronomy 26:1-11

Psalm 91:1-2, 9-16

Romans 10:8b-13

Luke 4:1-13

Prayer of the Day: O Lord God, you led your people through the wilderness and brought them to the promised land. Guide us now, so that, following your Son, we may walk safely through the wilderness of this world toward the life you alone can give, through Jesus Christ, our Savior and Lord, who lives and reigns with you and the Holy Spirit, one God, now and forever.

“Jesus, full of the Holy Spirit, returned from the Jordan and was led by the Spirit in the wilderness, where for forty days he was tempted by the devil. He ate nothing at all during those days, and when they were over, he was famished.” Luke 4:1-2.

Fasting is altogether incomprehensible in our present day culture. Commerce is geared toward satisfying appetites as soon as they arise, whether they stem from hunger, sexual desire or a craving for the latest i-doohicky from Apple. The very idea that a person would refrain from feeding an appetite strikes us as absurd. When you have an appetite, you feed it. That’s why we have fast food. When you want to know something, Google it. The answer is at your fingertips. Want something and can’t afford it? That’s the beauty of credit and Amazon. Punch a few keys and what you want arrives at your doorstep within hours. No more waiting for things, sacrificing for things, saving for the future. You can have it all right now.

Of course, there is something lost here. Yes, washing and peeling fresh vegetables, cooking a pork roast to perfection, mashing potatoes, setting the table, getting the whole family together, pausing for a word of thanksgiving-all of that takes time, energy and discipline. When your stomach is growling, it might seem a lot simpler just to order a pizza. But there is more to a meal than satisfying a primitive appetite. A meal is about providing nourishment that builds a healthy body; it is about togetherness with family and loved ones; it is about recognizing that food, family and community are gifts that belong together. We do not live by bread alone and when we try to live that way, we starve ourselves to death at the deepest level.

Rev. Nadia Boltz-Weber, a pastor in my own denomination (ELCA), a stand up comedian and author, recently wrote an article published in the Christian Century entitled “Talking to My Children About Sex Without Shame.” Pastor Boltz-Weber laments the church’s failure to “embrace the reality” that our teenagers are sexually active and to take the initiative in providing them with guidance and information they need to avoid STDs, unanticipated pregnancies and sexual exploitation. Those of you who follow this blog know that I am 100% on board with sex-ed for children and the availability of confidential medical advice, contraception and medical care, including abortion, for women of all ages. See my post, “What it Means to be Pro-Life.” I also agree with the pastor wholeheartedly when she points out that rules, whether religious, societal or civil, cannot protect our children from the dangers of our highly sexualized culture or give them the guidance they need to negotiate it. But shouldn’t we have more to say about the mystery of sex than physiology, safety and sanitation?

When it comes to having “the talk” with one’s children about sex, Pastor Boltz-Weber is refreshingly honest about her own experience: “I wanted to do better [than my parents] when I had kids. …[But] when it was my turn to have the sex talk with my own, I had no idea how to do it, either. Here, have a look:

2006: I mean to have “the talk” with Harper.

2007: I mean to have “the talk” with Harper.

2008: I mean to have “the talk” with Harper and Judah.

2009: The kids’ dad and I buy them each a book, hand it to them, and tell them to come to us if they have questions.

For all my big talk now about the things we can teach our children about sex, this was the extent of the sex talk I gave my kids when they were young.”

As a parent who has “been there,” I understand the difficulty of discussing sex with one’s children. But I don’t believe that difficulty arises from any sense of shame or discomfort we have with discussing penises, vaginas, orgasms, masturbation, rubbers or whatever else. I believe the root problem is that, like food, sex has become thoroughly divorced from its communal context. With the advent of reliable and widely available birth control coupled with the growing economic independence and opportunities for women in society, sex has become increasingly untethered from reproduction and married life. What, then, does a sexual act mean? Because we don’t really have a very good answer to that question, we find it difficult to discuss whatever parameters there might be for sexual expression. Indeed, it is hard to make the argument that there ought to be parameters if, like hunger, sexual desire has become only another appetite to be appeased. Why does it matter whether you get relief in the context of a long term relationship, a short term arrangement or a casual encounter? About the only requirement for sexual expression that we still seem to agree upon is mutual consent.[1]

I recently listened to a pastor addressing a group of us clergy on the topic of “story telling.” She related to us a story about how she wound up writing a funeral sermon in a hotel room following a one night stand with someone she met online. Perhaps we were all in a state of communal shock, but no one questioned the propriety of this liaison. At the time, I was a little taken aback. Upon further reflection, however, I had to wonder whether it is any more blameworthy to satisfy one’s sexual longings in a one night stand than it is to satisfy one’s appetite in the privacy of your car on the other side of the Wendy’s drive thru? If appetite is all there is to it, why not?[2]

Because, says Jesus, we do not live by bread alone. Eating isn’t just about food. Sure, we have the ability to satisfy our hunger whenever we wish and, unlike Jesus, we don’t even have to go to the trouble of turning stones into bread. But there is something off-you might even say demonic-about eating one’s bread in isolation. However much we may have separated ourselves from the soil and toil of our neighbors who grow, harvest and bring our food to places where it is processed for our own convenience; however much we may have convinced ourselves that we have provided for ourselves out of our own work and resourcefulness; and however much we have let the gods of convenience and efficiency deter us from communal meals, the fact remains that the food sustaining our lives is a gift from the One who gave us our lives. Food is not given merely to be consumed, but to be shared. As anyone who reads the Bible knows, meals are the cornerstone of community. The church is built around the meal we call Eucharist. We are the people who “spen[d] much time together” and “break bread at home, eating with glad and generous hearts.” Acts 2:46.

I believe we fast in order to give the Holy Spirit an opportunity to teach us the critical difference between genuine hunger and mere appetite. Our hunger is so much deeper and our need so much more profound than we know. We will never come into that holy hunger that only God can fill unless we are prepared to empty ourselves. We will never find fulfillment of our deepest needs unless we free ourselves from the tyranny of our appetites. Fasting can help us rediscover the meaning of bread in the fellowship of family, in the community of faith and in the very person of Jesus who is our bread. From that vantage point, perhaps we can also begin to reflect on many of the other appetites that blind us to our deeper hunger.

I don’t believe the church has any stock answers for our current disconnect with our sexuality. The moral rules we have inherited come from a time when coital sex always carried with it the potential for pregnancy, where women had no independent legal existence apart from the men to whom they belonged and when the institution of marriage served the salutary purpose of protecting vulnerable women and children. I don’t believe anyone in their right mind would want to return to that state of things even if it were possible. Nonetheless, I believe that our sexuality needs desperately to be grounded in meaning. Until that happens, we only spin our wheels trying to frame moral rules and social conventions. What the church can offer are its tried and true disciplines through which the Spirit creates and sustains communities capable of reflecting on our sexuality (and so many other dimensions of our existence) and contextualizing it. The season of Lent lifts up those disciplines and invites us to explore together the nature of our deepest hungers, the generosity of the God who promises to satisfy them and the way forward to a new day through repentance, forgiveness and reconciliation.

Here are two poems, one by Jonathan Holden speaking to the emptiness of loveless sex and the other by Ellen Bass hinting at what sexual expression can be.

Sex Without Love

If evil had style

it might well resemble

those pointless experiments

we used to set up and run

with our legs and our hands

and our mouths between two

and four p.m. while our kids

were swimming in the public pool

and our wives, our husbands,

were somewhere else-

an hour when nobody wanted

to move, the heat

had gone breathless, slack

as if the afternoon

had been punched in the stomach,

a victim of what we’d coolly

decided to do. There might

be the nagging of a single mower.

At last even that would die

in the heat. Would catch

a rumor of thunder in the hills-

a signal, like the smirk

of swallowed amusement you’d slip

my direction by raising just

slightly your eyebrows as much

as to ask, Well, Shall we?

It’s a style might well resemble

the wholly gratuitous gear

we would then shift down to

as deliberately we would undress,

our eyes wide open without

compromise, curious to observe what

a body might be up to next

on such a hopeless afternoon,

just barely affection

enough-a pinch of salt-

to produce that sigh, when

for a lucky moment or so

curiosity can be mistaken

for enthusiasm and we learn

what we already know.

Source: Poetry, June 1985

Marriage

When you finally, after deep illness, lay

the length of your body on mine, isn’t it

like the strata of the earth, the pressure

of time on sand, mud, bits of shell, all

the years, uncountable wakings, sleepings,

sleepless nights, fights, ordinary mornings

talking about nothing, and the brief

fiery plummets, and the unselfconscious

silences of animals grazing, the moving

water, wind, ice that carries the minutes, leaves

behind minerals that bind the sediment into rock.

How to bear the weight, with every

flake of bone pressed in. Then, how to bear when

the weight is gone, the way a woman

whose neck has been coiled with brass

can no longer hold it up alone. Oh love,

it is balm, but also a seal. It binds us tight

as the fur of a rabbit to the rabbit.

When you strip it, grasping the edge

of the sliced skin, pulling the glossy membranes

apart, the body is warm and limp. If you could,

you’d climb inside that wet, slick skin

and carry it on your back. This is not

neat and white and lacy like a wedding,

not the bright effervescence of champagne

spilling over the throat of the bottle. This visceral

bloody union that is love, but

beyond love. Beyond charm and delight

the way you to yourself are past charm and delight.

This is the shucked meat of love, the alleys and broken

glass of love, the petals torn off the branches of love,

the dizzy hoarse cry, the stubborn hunger.

Source: Poetry, April 2018

Jonathan Holden (b. 1941) is a Professor of English at Kansas State University, Manhattan, Kansas. He was born in Morristown, New Jersey and received a bachelor’s degree in English from Oberlin College. From 1963 to 1965, he was an editorial assistant for Cambridge Book Company in Bronxville, New York. He then taught math at a high school in West Orange, New Jersey for two years. Holden received an master’s degree in creative writing from San Francisco State College and a Ph D in English from the University of Colorado. He was poet-in-residence at Stephens College in Columbia, Missouri. In 1978 he joined Kansas State University. He has served on the Pulitzer Prize poetry selection committee and was appointed poet laureate by the governor of Kansas in 2004. You can find out more about Jonathan Holden and sample more of his poetry at the Poetry Foundation Website.

Ellen Bass (b. 1947) is an American poet and co-author of The Courage to Heal. She grew up in Pleasantville, New Jersey where her parents owned a liquor store. Her family later moved to Ventnor City, New Jersey. She earned her bachelor’s degree at Goucher College and pursued a master’s degree in creative writing at Boston University where she studied with poet, Anne Sexton. Bass currently lives in Santa Cruz, California where she teaches creative writing. You can learn more about Ellen Bass and sample more of her poetry at the Poetry Foundation Website.

[1] Consent is not the clear cut standard we sometimes imagine it to be. In most states, teenagers are deemed legally incapable of consent to sexual activity. Moreover, we might rightly ask what consent even means in our sexualized and patriarchal culture where the president of the United States can assert without any loss of support that, as a celebrity male, he is entitled to grab any girl he wishes by the genitals.

[2] In fairness to the speaker, I think she was at least hoping that her encounter might blossom into a deeper relationship. Yet I still have to wonder what meaning sex has in the context of such a tenuous encounter. Is it anything more than another form of mutual entertainment, such going to a movie or taking a walk on the beach?