FIRST SUNDAY OF ADVENT

Prayer of the Day: Stir up your power, Lord Christ, and come. By your merciful protection waken us to the threatening dangers of our sins, and keep us blameless until the coming of your new day, for you live and reign with the Father and the Holy Spirit, one God, now and forever.

“[God] will also strengthen you to the end, so that you may be blameless on the day of our Lord Jesus Christ.” I Corinthians 1:8.

OK. It was cheesy, simplistic, inconsistent with astrophysics and woefully lacking in cinematic effects judged by today’s standards. But it was hopeful, idealistic and forward looking. I am speaking of the original Star Trek series that aired on NBC from 1966-1969. Its producer, Gene Roddenberry, managed to create a universe in which racial, ethnic and geopolitical strife had been overcome on a planet earth united and playing a leadership role within the fictional United Federation of Planets. There were, to be sure, continuing vestiges of prejudice to be addressed. In one episode, Captain Kirk must remind a crew member, suspicious Vulcan first officer Spack’s loyalty, that “bigotry will not be tolerated on this ship.” Yet even this testified to the show’s forward looking world view. Yes, there were still sexist stereotypes, i.e., female officers attired in miniskirts and usually in subordinate positions. True, the twenty-third century communicators were clunkier than our 1990s flip phones, to say nothing of the smart phone. But the overall message still rings clear. The future lies in global unity, scientific inquiry and ever increasing understanding of the universe.

Watching the re-runs today, it is hard for me to imagine this series catching on in today’s culture. Perhaps that is why the subsequent Star Trek series tended to be darker, more cynical and less hopeful. So far from a future characterized by a united globe pressing forward to encounter new civilizations where “no man has gone before,” ours is a world where, at home and abroad, the cries of “nation first” and anti-global sentiment are on the rise. Argentina is the latest nation to succumb to fascist populism, joining nations in eastern Europe. Fascism has largely taken over the Republican party[1] and appears poised to seize power in the upcoming election. The old gods of nation, race, blood and soil have all but swallowed up hope for a peaceful and united planet. Indeed, “globalism” is now the major hobgoblin of the populist right.

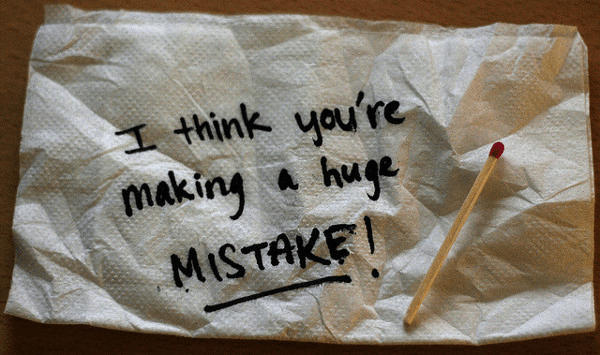

These fascist ideologues have one thing in common. They are all convinced that the future is in the past, a place in time when all was right with the world and to which we need somehow to get back. Call this “againism.” There was a time before LGBQT+ folk came out of the closet and ruined the institution of marriage; a time before black men forgot their place and started taking our jobs, filling up our television screens with their faces and started dating our women. There was a time when English was the only language you ever saw on a sign. There was a time when the way a man chose to discipline his family was his own damn business and the cops, school teachers and nosey social workers didn’t interfere. There was a time when women respected their men, dressed like women and stuck to the woman’s natural work of homemaking instead of trying to wear pants to a man. That golden age, that time when the country was great, has been stolen from us and we have to take it back. We have to make America great “again.” If you have any doubts about precisely what that means, the leader of the Republican party made that very clear to us on his media platform, Truth Social: It means to “root out the Communists, Marxists, Fascists, and Radical Left Thugs that live like vermin within the confines of our country.”[2] Only then will America be great-again.

Againism is, of course, a dead end. A future in some imaginary past is not in the cards. It won’t happen. There are too many of us vermin to extinguish, no matter how many of us are killed in the service of futile efforts to get back to “again.” Adolph Hitler couldn’t bring back the mythical golden age of Aryan supremacy and neither can that sad little Mussolini wannabe down in Mar-a-Lago. That might seem like cold comfort and, by itself, it is. But there is more. There is a future. It is not in the past and it belongs to the God who raised Jesus from death. Unlike the “againist” longing for a purified nation, untainted blood and changeless cultural norms which is so lame and fragile that it must be defended by border walls, racial gerrymandering and the banning of books, God’s future is radically inclusive, culturally diverse and wide open:

“After this I looked, and there was a great multitude that no one could count, from every nation, from all tribes and peoples and languages, standing before the throne and before the Lamb, robed in white, with palm branches in their hands. They cried out in a loud voice, saying,

‘Salvation belongs to our God who is seated on the throne, and to the Lamb!’

And all the angels stood around the throne and around the elders and the four living creatures, and they fell on their faces before the throne and worshipped God, singing,

‘Amen! Blessing and glory and wisdom

and thanksgiving and honor

and power and might

be to our God for ever and ever! Amen.’” Revelation 7:9-12

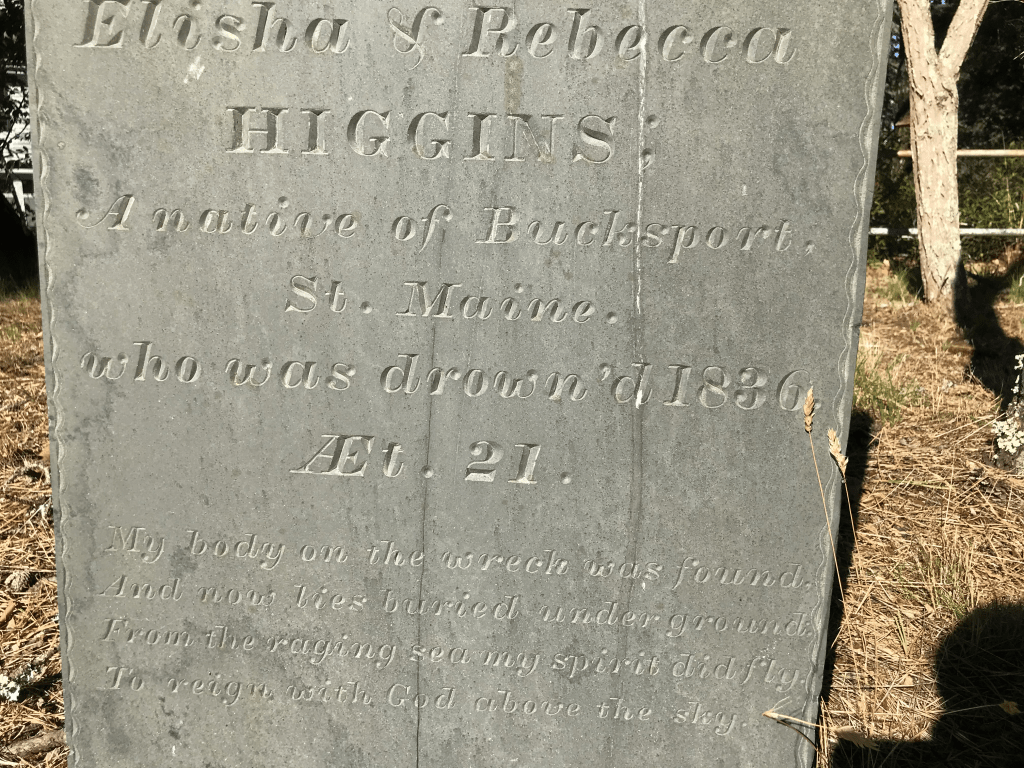

Hanging onto that vision of inclusiveness and global kinship is difficult in times like ours when it seems as though our world is dissolving into nationalism, tribalism and sectarian violence. It was no less so for Jesus’ disciples who weathered the final days of their nation’s occupation and brutal destruction. I can well understand their wanting Jesus to tell them “when will this be, and what will be the sign when these things are to be accomplished?” Mark 13:4. But Jesus will not give them either a map or an itinerary. Not only will the temple of Jerusalem be destroyed, but there will be wars, rumors of war, earthquakes and famines. These events will convince many that the end must be near. They are mistaken. No one knows the “when.” Not even Jesus. Mark 13:32. What Jesus does know and what he tells his disciples is that there will be a long road of suffering during which they must bear witness to the just, gentle and peaceful reign of God he proclaims in the midst of rival kingdoms each bent on dominance and control. Those who cling to that vision, who endure to the end will be saved.

All of this might sound bleak, but there is more than a glimmer of good news in all of this. Jesus tells us that all of these dread events are not death throws, but birth pangs. God is at work forging a new creation in the midst of this troubled world. Just as God turned a violent, oppressive and cruel Egyptian empire into the womb within which the people of Israel were birthed and freed, just as Jesus’ death and resurrection transformed the Roman Empire’s symbol of terror into a sign of victory, so you can be sure that God will turn the violence of our nation’s and the world’s racism, xenophobia, patriarchy and homophobic violence into yet another demonstration of its utter impotence. That might take some time. But God has all eternity to work with.

Ultimately, today’s gospel is, above all else, hopeful. I think that is the right note on which to enter the season of Advent. After all, the failed religion of “againism” is a religion of despair and desperation. It is a religion that lives in terror of the future and spends itself in a fruitless effort to keep it at bay. The good news Jesus brings assures us that the future is not to be regarded with dread, but embraced in hope, a hope enabling one to endure until it is finally realized in its fullness.

Here is a poem that speaks elequently of hope by Emily Dickenson. It sounds the hopeful note on which we ought to enter this new church year.

Hope is a Thing with Feathers

“Hope” is the thing with feathers –

That perches in the soul –

And sings the tune without the words –

And never stops – at all –

And sweetest – in the Gale – is heard –

And sore must be the storm –

That could abash the little Bird

That kept so many warm –

I’ve heard it in the chillest land –

And on the strangest Sea –

Yet – never – in Extremity,

It asked a crumb – of me.

Source: The Poems of Emily Dickinson: Reading Edition, (c. 1999 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College; edited by Ralph W. Franklin, ed., Cambridge, Mass.) Emily Dickinson (1830-1866) is indisputably one of America’s greatest and most original poets. Born in Amherst, Massachusetts, she attended a one-room primary school in that town and went on to Amherst Academy, the school out of which Amherst College grew. In the fall of 1847 Dickinson entered Mount Holyoke Female Seminary where students were divided into three categories: those who were “established Christians,” those who “expressed hope,” and those who were “without hope.” Emily, along with thirty other classmates, found herself in the latter category. Though often characterized a “recluse,” Dickinson kept up with numerous correspondents, family members and teachers throughout her lifetime. You can find out more about Emily Dickinson and sample more of her poetry at the Poetry Foundation website.

[1] I fear my Republican friends might take offense to this characterization of their party. Too bad. You have demonstrated again and again that, as much as you might loath Donald Trump, as long as the clear majority of your party supports him, you will support him also. With the exception of former New Jersey governor Chris Christi, every single Republican nominee pledged to support Donald Trump should he be nominated by their party-and to pardon him of every crime he might be found guilty in the unlikely event they themselves should be elected. If you haven’t the courage and initiative to fix up your home, don’t complain that people criticize you for living in a dump.

[2] To be fair, Donald Trump’s campaign representative, Steven Cheung, pointed out that these remarks were not threatening in the least. Those who are concerned about Trump violently attacking his opponents are suffering from “Trump Derangement Syndrome.” What Trump really meant to say of his political opponents, says Cheung, was that “their entire existence will be crushed when President Trump returns to the White House.” Whew! I feel so much better now!