SIXTH SUNDAY OF EASTER

Prayer of the Day: O God, you have prepared for those who love you joys beyond understanding. Pour into our hearts such love for you that, loving you above all things, we may obtain your promises, which exceed all we can desire; through Jesus Christ, your Son and our Lord, who lives and reigns with you and the Holy Spirit, one God, now and forever.

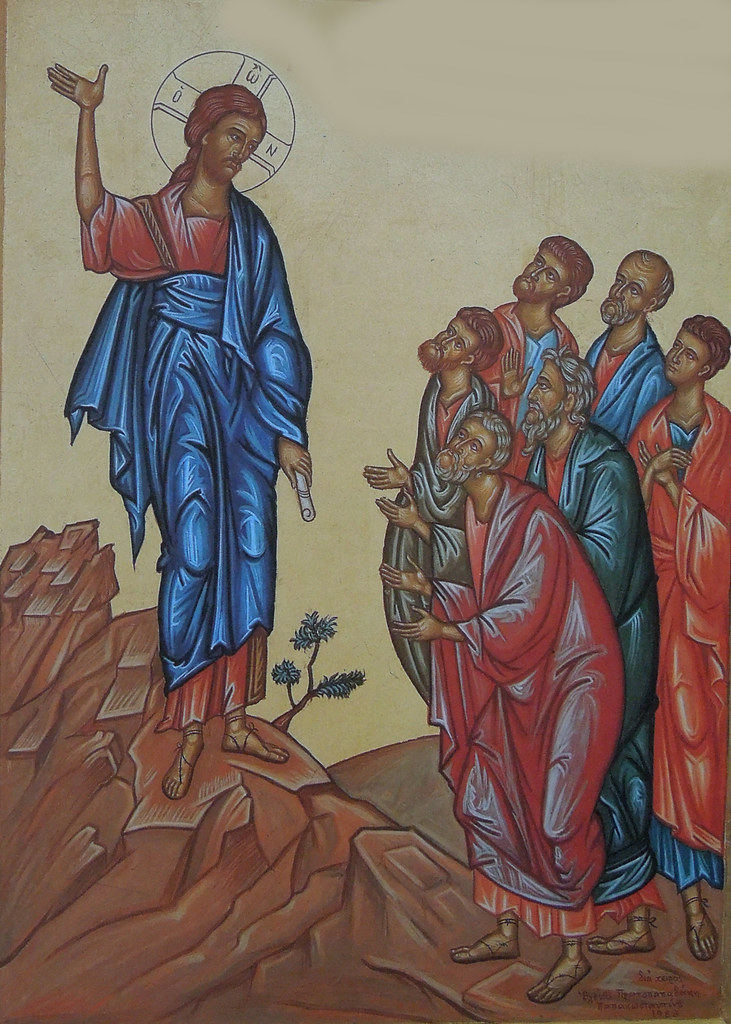

“As the Father has loved me, so I have loved you; abide in my love.” John 15:9.

Brad is a tall, lanky kid with some troubling mental impairments. On any given Sunday morning you can find him in the narthex pacing back and forth looking for a conversation partner. If you are wise, you will not make eye contact because as soon as you do, Brad will latch onto you and start talking-nonstop. Brad has no sense of personal bubble. He will get right in your face. To make matters worse, he has halitosis powerful enough to slay an ox. Unless you are willing to be less than courteous, you will not escape before the start of the service. If Brad is the first person you meet when visiting our church, you might consider going somewhere else next Sunday.

Sally is generally friendly, cheerful and sociable. But there are days when she comes to church with all the fears and phobias her medication is supposed to keep in check. On those days, she might approach you and ask, “Why are you staring at me? What were you telling that lady about me? I heard the names you just called me! You’re very poor Christian to talk like that about me.” There is nothing you can say to disabuse her of her conviction that you are out to get her. If Sally is the first person you run into when visiting our church, chances are good you will not be back next week.

Bernie is a crabby octogenarian who comes to church with his daughter. He complains audibly about the slightest noise any child might make, makes rude remarks to anyone sitting in what he imagines to be “his” pew and mutters throughout the service about how he wishes people would speak up so that they can be heard. Bernie’s politics is extreme to the point of falling off the edge of the flat earth. He is not shy about expressing his views as well as his contempt for all who do not share them, which probably includes you. If you have the misfortune of sitting near Bernie on your first visit to our church with your children, you will not come away with a good first impression.

So here is my problem with the notion that the church is supposed to be a “welcoming community.” Every church I have served has people like Brad, Sally and Bernie. They are members of our congregation because nobody else will have them. Nowhere else will anyone put up with their antics. They annoy the hell out of us, too. But they belong to us. They are part of our household of faith. We believe that they are with us because Jesus has called them here. We believe they have things to teach us that we cannot learn from anyone else. So we love them, as difficult as that sometimes is. I am mighty proud (in a Pauline sense of the word) of our church for that very reason. Consequently, if you are to be a part of our church, you must learn to love them too.

As I know I have said before, one of the big mistakes we American protestants make is overselling the church and underselling Jesus. Look to the religion section of any local paper and you will find churches advertising their friendliness, lively worship, community activism, youth programs, couples’ groups, singles groups, quilting groups and all manner of cultural and social events. The programmatic welcome mat is out. My own ELCA advertises itself on our website as a church that “embrace[s] you as a whole person–questions, complexities and all.” What we do not say on that website, though perhaps we should, is that we expect the same in return. If you cannot embrace Brad, Sally and Bernie, then my church is not the place for you. We are not the loving and affirming family you never had. We are not a place safe from insult, hurt and rejection. If you want a community where everyone affirms you, everyone strives to meet your needs, everyone makes you feel comfortable, accepted and at ease, then I recommend Sandals, Club Med or a yoga retreat in the Poconos. Church is not about making you welcome, at ease and comfortable. It is about making you a saint.

Jesus tells his disciples, “[t]his is my commandment, that you love one another as I have loved you.” John 15:12. It grates on our modernistic ears when Jesus uses “love” and “commandment” in the same breath. Love cannot be compelled, can it? Love should be given freely, spontaneously and without coercion. Otherwise, it is not truly love, is it? That, not to put too fine a point on it, is a bunch of Hallmark crap. The love Jesus is talking about is a matter of action, not words. As John the Evangelist pointed out to us last week, all the pity, compassion and love we might have for our hungry siblings is empty sentimentality if we do not come across with something into which those siblings can sink their teeth.

Love is a spiritual discipline. It develops with practice. Sometimes before you can love someone, you have to act like you do. You need to put up with a lot, forgive a lot, try and fail a lot before you finally begin to know people, learn their stories, understand their struggles and see them for the unique and fascinating individuals they are. It takes a long time before understanding breeds compassion, compassion breeds caring and caring grows into love. Love is not something you fall into. It is like learning a musical instrument. A lot of practice lies between picking up the violin for the first time and the concert performance. Abiding in love is damned hard work. If you are not up for that, church is not the place for you.

I meet a lot of folks these days who accuse the church of hypocrisy because we do not live up to the love we profess. In such encounters, I feel very much like Inigo Montoya from the movie, The Princess Bride, who famously said “[y]ou keep using that word. I do not think it means what you think it means.” If Christians are hypocrites because they do not meet the standard of love to which they aspire, then every Olympic athlete competing for gold, but who comes away with silver or bronze instead is a hypocrite. Every student who ever aspired to get an A but managed only a B is a hypocrite. Hypocrites, according to this warped understanding, are people with high aspirations pushing them to become better, stronger and more courageous than they are. In fact, however, hypocrites are those who claim to have reached aspirational goals that they have not actually met. They are people who pretend to be better than they truly are. To be sure, there are hypocrites in the church as there are everywhere else. But in defense of hypocrites, I will say they have at least enough of a moral compass left to be ashamed of the failures they try to cover up. More revolting than hypocrites are those who admit to having no standards and take a cynical pride in mocking those who do by remarking, “well, unlike all the hypocrites, at least I’m honest!” Here the words of Francois Duc De La Rochefoucauld ring true: “Hypocrisy is a tribute that vice pays to virtue.”

A more honest (dare I say less hypocritical?) portrayal of the church (are you listening ELCA?) would be to say that we are a community of flawed people who have been embraced as whole persons–questions, complexities and all by a God who loves us completely, freely and unconditionally. We strive, often with only limited success, to love as we have been loved, to follow Jesus in giving ourselves to humble service and truthful witness in word and deed. We invite you to join us on our journey to becoming the people our God would have us be. But be prepared for hurt feelings, insults, rejection and misunderstanding. That is all part of abiding in love with people who have not yet got it quite right, but are getting there little by little. This is boot camp for learning love. Are you up for that?

Here is a poem by Julia Kasdorf about church and the way love is learned, practiced and grows.

What I Learned from my Mother

I learned from my mother how to love

the living, to have plenty of vases on hand

in case you have to rush to the hospital

with peonies cut from the lawn, black ants

still stuck to the buds. I learned to save jars

large enough to hold fruit salad for a whole

grieving household, to cube home-canned pears

and peaches, to slice through maroon grape skins

and flick out the sexual seeds with a knife point.

I learned to attend viewings even if I didn’t know

the deceased, to press the moist hands

of the living, to look in their eyes and offer

sympathy, as though I understood loss even then.

I learned that whatever we say means nothing,

what anyone will remember is that we came.

I learned to believe I had the power to ease

awful pains materially like an angel.

Like a doctor, I learned to create

from another’s suffering my own usefulness, and once

you know how to do this, you can never refuse.

To every house you enter, you must offer

healing: a chocolate cake you baked yourself,

the blessing of your voice, your chaste touch.

Source: Sleeping Preacher (c. by Julia Kasdorf, 1992; pub. by University of Pittsburgh Press). Julia Kasdorf (b. 1962) is a Poet, essayist, and editor. She was born in Lewistown, Pennsylvania and received her BA from Goshen College. She earned an MA in creative writing and a PhD from New York University. She is the editor for the journal, Christianity and Literature and author of several books of poetry. You can find out more about Julia Kasdorf and read more of her poetry at the Poetry Foundation website.