THIRD SUNDAY OF EASTER

Prayer of the Day: Holy and righteous God, you are the author of life, and you adopt us to be your children. Fill us with your words of life, that we may live as witnesses to the resurrection of your Son, Jesus Christ, our Savior and Lord, who lives and reigns with you and the Holy Spirit, one God, now and forever.

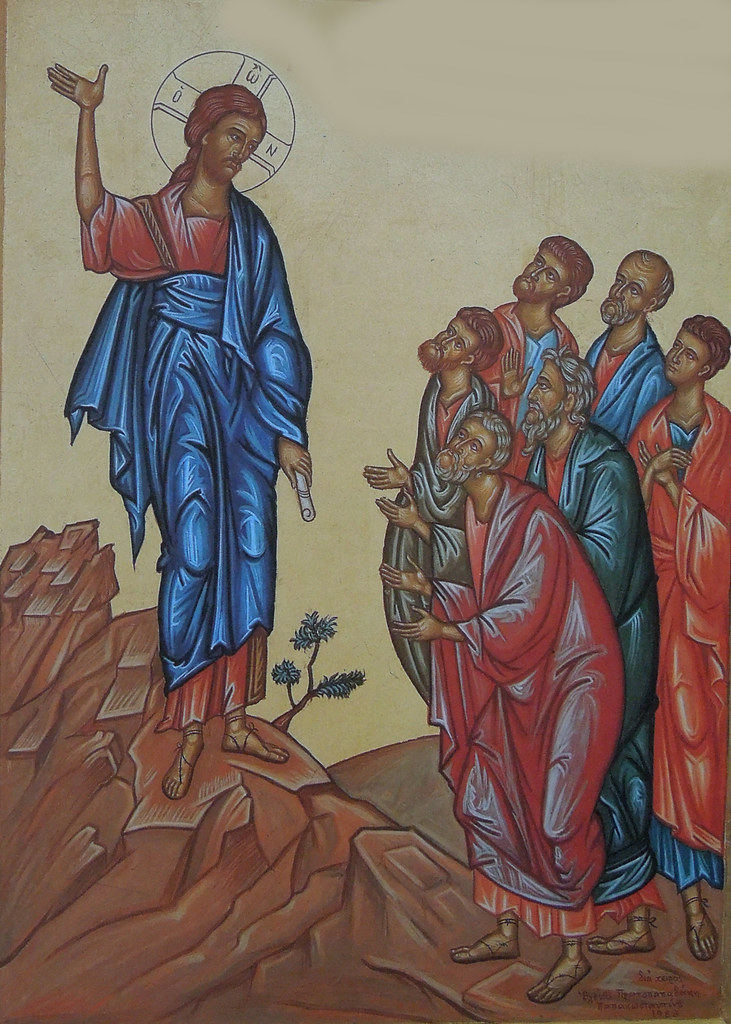

“Thus it is written, that the Messiah is to suffer and to rise from the dead on the third day, and that repentance and forgiveness of sins is to be proclaimed in his name to all nations, beginning from Jerusalem. You are witnesses of these things.” Luke 24:46-48.

So ends the Gospel of Luke-and so continued its sequel, the Book of Acts where Luke tells the story of how the church, which began as a local Jewish movement in Palestine, expanded into the heart of the Roman empire with the dream of reaching the end of the known world. The path was fraught with linguistic differences, class distinctions, legal barriers and cultural differences. Saint Paul and his missionary companions and contemporaries were compelled to deal with difficult questions as they sought to proclaim the good news of Jesus Christ to communities of the Jewish diaspora that had never heard of Jesus and knew nothing of his ministry. So, too, they struggled to make that good news intelligible to non-Jewish audiences that did not know the ancient scriptural narratives about Israel’s God and had no idea what a “messiah” was.

It was not smooth sailing. Saint Paul insisted that his gentile converts be received into the church as they were, without having to undergo circumcision or observe the ritual and dietary requirements of Israel’s faith tradition. From Paul’s perspective, the good news that is Jesus welcomed everyone into God’s redemptive covenant on the same terms, namely, through faith in God’s promises. Faith in Jesus alone made disciples of Jew, gentile, male, female, slave, free, citizen and non-citizen. After all, Abraham’s faith saved him before Israel, circumcision and the Torah existed. Why should more than faith be required to save anyone else?

Paul, however, experienced stiff resistance from within the church. In his letter to the Galatian church, he recounts a dispute he had with Saint Peter and Saint James over their segregation in table fellowship between Jewish and gentile believers. This practice outraged Paul. If there is but one Body, how can there be two tables? This was a point on which Paul could not compromise. As far as he was concerned, the integrity of the gospel was at stake. For many Jewish believers, both within and outside the church, Paul’s radical invitation for gentiles to enter into Israel’s covenant relationship with God without requiring their participation in Israel’s faith traditions was a bridge too far. Luke’s account in the Book of Acts indicates that Paul’s openness to receiving gentile believers led finally to his arrest, imprisonment and journey to Rome in chains to be tried before the emperor’s tribunal.

Being a life-long Lutheran, I have always tended to side with Paul. If there is one thing every Lutheran agrees on, wherever on the spectrum of high church, low church, conservative or liberal we may fall, it is this: Salvation is by grace alone through faith in Jesus Christ. God’s gifts of forgiveness, sanctification and eternal life can never be earned. They can only be received with gratitude and joy. Of course, I still subscribe to that assertion. But I have also developed a more sympathetic view of Paul’s critics. They were concerned, rightly I believe, that the good news of Jesus Christ was losing its grounding in the scriptures and traditions of Israel. Paul’s critics believed that the faithful life, obedient death and glorious resurrection of Jesus could never be understood rightly apart from its Jewish roots. Without the stories of the matriarchs and patriarchs, Moses and the Exodus, the Torah and the testimony of the prophets, “faith in Jesus” too easily becomes a mere abstraction. It is too readily reduced to mere intellectual assent to a doctrinal proposition.

Saint James recognized this danger and addressed it pointedly:

“But someone will say, ‘You have faith and I have works.’ Show me your faith without works, and I by my works will show you my faith. You believe that God is one; you do well. Even the demons believe—and shudder. Do you want to be shown, you senseless person, that faith without works is barren? Was not our ancestor Abraham justified by works when he offered his son Isaac on the altar? You see that faith was active along with his works, and faith was brought to completion by the works. Thus the scripture was fulfilled that says, ‘Abraham believed God, and it was reckoned to him as righteousness’, and he was called the friend of God. You see that a person is justified by works and not by faith alone. Likewise, was not Rahab the prostitute also justified by works when she welcomed the messengers and sent them out by another road? For just as the body without the spirit is dead, so faith without works is also dead.” James 2:18-26.

The above passage is the least favorite among us Lutherans. Indeed, Martin Luther is known to have referred to the Letter of James as “an epistle of straw.” But I believe James points to a danger that Paul may have failed to appreciate and that has, in fact, done great damage. Abstraction is not the only evil to arise from divorcing the gospel of Jesus Christ from its Jewish roots. Though hardly what Saint Paul intended, as the rift between the church and the synagogue grew, the New Testament began to be understood by the church as a repudiation rather than a commentary on the Hebrew Scriptures. Naturally, this implied a repudiation of Judaism as well. Read in the context of a gentile church now recognized as the religion of the empire and separate from the Jewish community, the gospels, and the Gospel of John in particular, take on a decidedly darker interpretation of Judaism. Rather than the beloved community of Israel in whose traditions Jesus understood himself and was understood by his disciples, “the Jews” become opponents of Jesus, enemies of the gospel and “Christ killers.” Luther’s vile rants against the Jews remain a painful and disgraceful stain on my own spiritual heritage as does our complicity in Europe’s horrendous history of antisemitic violence culminating in the Holocaust. However misguided they may have been in many respects, I believe that Paul’s critics were onto something important. Perhaps if Paul had been more attentive to and less confrontational with his critics and Martin Luther less dismissive of Saint Jame’s epistle, we might all have ended up in a much better place.

To be clear, I do not believe that Paul intended to divorce the gospel of Jesus Christ from its Jewish roots. Neither do I believe James is suggesting that salvation is a reward to be earned by works of the law or that faith is not enough to make faithful disciples. Like Paul, James recognized that “every generous act of giving, with every perfect gift, is from above, coming down from the Father of lights.” James 1:17. That would include faith. But James would have us know that faith is always embodied in the lives of the faithful. It is not a doctrinal proposition. Faith is a habit of the heart on full display throughout the Hebrew Scriptures in the lives of the faithful-both patriarchs and prostitutes. “The Jews” are not Jesus’ enemies. They are his people, his family, his siblings and his disciples. Without their witness, we can never properly understand and follow Jesus. That is why, prior to commissioning his disciples to preach the gospel to the whole world, Jesus “opened their minds to understand the scriptures,” which at this point could only have been the “the law of Moses, the prophets, and the psalms.” Luke 24:44-45.

For the sake of the gospel of Jesus Christ and for the sake of our spiritual siblings in Judaism, we need to recapture in our liturgy, preaching and teaching the centrality of the faith in which Jesus lived, the traditions that shaped his life and ministry and the people of whom he was a member and who he loved. Here is a poem by Karl Shapiro reflecting the pain inflicted upon the Jewish people as a result of our flawed readings and interpretations of the scriptures.

Jew

The name is immortal but only the name, for the rest

Is a nose that can change in the weathers of time or persist

Or die out in confusion or model itself on the best.

But the name is a language itself that is whispered and hissed

Through the houses of ages, and ever a language the same,

And ever and ever a blow on our heart like a fist.

And this last of our dream in the desert, O curse of our name,

Is immortal as Abraham’s voice in our fragment of prayer

Adonoi, Adonoi, for our bondage of murder and shame!

And the word for the murder of Christ will cry out on the air

Though the race is no more and the temples are closed of our will

And the peace is made fast on the earth and the earth is made fair;

Our name is impaled in the heart of the world on a hill

Where we suffer to die by the hands of ourselves, and to kill.

Source: Poetry, (August 1943). Karl Jay Shapiro (1913-2000) was an American poet. He was born and raised in Baltimore, Maryland. He attended the University of Virginia during the 1932-1933 academic year. In a critical poem reflecting on his experiences there, he remarked that “to hurt the Negro and avoid the Jew is the curriculum.” He continued his studies at the Peabody Institute, majoring in piano. He attended Johns Hopkins University from 1937 to 1939. In 1940, he enrolled in a library science school associated with Baltimore’s Enoch Pratt Free Library, where he was also employed. Shapiro served as a United States Army company clerk during World War II in the Pacific theater. During this time, he wrote many of the poems that propelled him into recognition. Shapiro never completed an undergraduate degree. Nonetheless, he was retained at Johns Hopkins as an associate professor of writing from 1947 to 1950. From 1950-1956 he served as editor of Poetry and as a visiting professor at the University of California, Berkeley and at Indiana University. In 1956 he left the editorship and taught English at the University of Illinois while editing the Prairie Schooner at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. He thereafter moved to the University of California, Davis, where he became professor emeritus of English in 1985. You can read more about Karl Shapiro and sample more of his poetry at the Poetry Foundation website