SEVENTH SUNDAY OF EASTER

Prayer of the Day: Gracious and glorious God, you have chosen us as your own, and by the powerful name of Christ you protect us from evil. By your Spirit transform us and your beloved world, that we may find our joy in your Son, Jesus Christ, our Savior and Lord, who lives and reigns with you and the Holy Spirit, one God, now and forever.

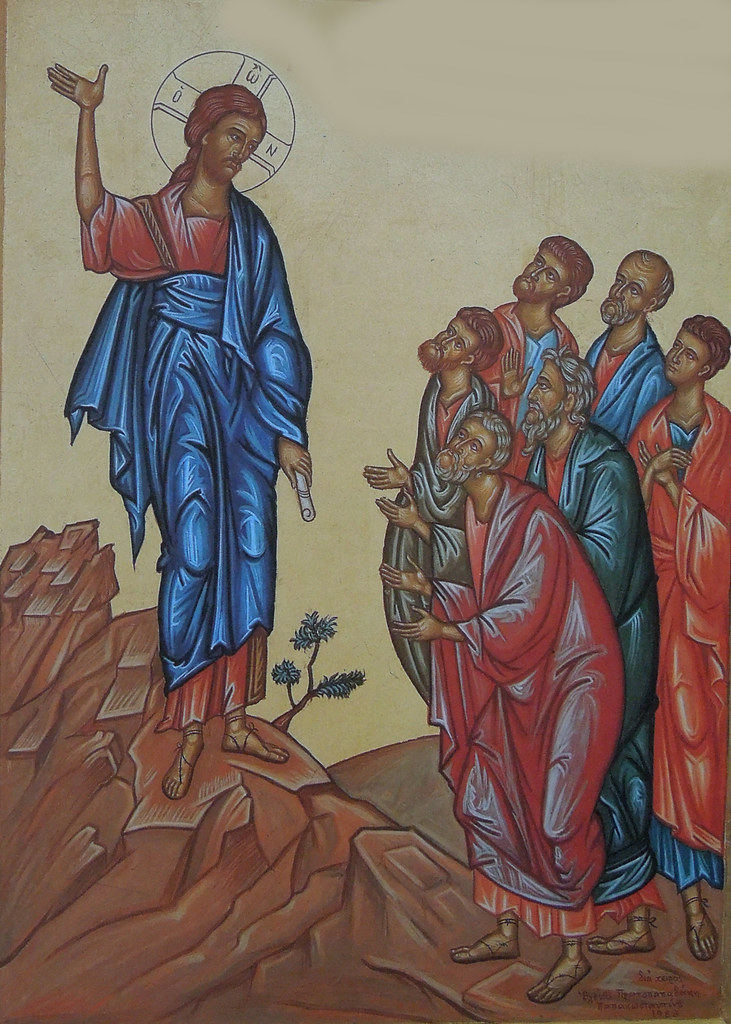

“And now I am no longer in the world, but they are in the world, and I am coming to you. Holy Father, protect them in your name that you have given me, so that they may be one, as we are one.” John 17:11.

“Happy are those

who do not follow the advice of the wicked,

or take the path that sinners tread,

or sit in the seat of scoffers;

but their delight is in the law of the Lord,

and on his law they meditate day and night.” Psalm 1:1-2.

“There are two ways, one of life and one of death, and there is a great difference between the two ways. The way of life is this. First of all, thou shalt love the God that made thee; secondly, thy neighbor as thyself.” The Didache

“There are two ways…” says the anonymous ancient early Christian epistle, The Didache. That sentiment is reflected in the psalm and Jesus’ words in this Sunday’s gospel reminding us that disciples of Jesus remain “in the world.” Lest there be any misunderstanding here, this is the same world to which God sent the only Son to save and not condemn. Yet it is a world hostile to God, so hostile in fact that it rejected and murdered the most precious gift God had to give. It is a world governed by a culture of human greed and retributive violence. In the midst of this world, disciples of Jesus are invited to become a counter-cultural community governed by love. The church is to be, as Koinonia Farms founder Clarance Jordan once remarked, a “demonstration plot” for the kingdom of God. It is the place where Jesus invites us to recover our humanity, to have the mind of Christ formed in us, to regain the divine image in which we, along with all humanity, were created. The good news of Jesus is that there is a better way of being human, a better way for the world to be the world. This, according to our lessons and the Didache, is the way of life.

It may appear that the choice between “the two ways” is a once and for all decision. Or perhaps it presents itself only in circumstances where the choice literally involves either life or death, such as it did for those few heroic souls in occupied Europe during the Second World War who risked their lives sheltering Jews in their homes from the Nazis. Such occasions constitute the “moment of truth,” the time of trial that defines who a person truly is. But that is not really the case. Contrary to popular lore, the devil never buys a soul outright in a single transaction. He takes it piece by piece, one small moral decision at a time. Just as courage, integrity and honesty are habits of the heart formed by the practice of small, daily ordinary acts of selfless compassion that build character capable of standing firm in the time of trial, so these virtues are stolen one white lie, one practical compromise with evil, one small theft, one inconsequential act of deception at a time.

I know whereof I speak. I have taken a stroll on the path of death myself. For eighteen years I practiced law at a firm specializing in civil defense. We were employed by insurance companies to defend their policyholders against law suits ranging from professional liability claims to simple slip and fall cases. I feel compelled to say from the outset that my firm’s record and reputation for ethics cannot be matched. We were nothing if not scrupulous when it came to honesty with our clients, honesty with the court and honesty and fairness toward our adversaries in the litigation process. But as everyone knows, most cases are not resolved through the formal litigation process. Typically, civil cases are settled at some point before trial through negotiation. Attorneys representing the plaintiff usually initiate negotiations by making a settlement demand far in excess of what they actually expect to get. Attorneys for the defendant, like me, will respond with a settlement offer far below what we actually believe will be required to resolve the case. “I am authorized to offer seventy-five thousand to put this matter to bed,” I say to the plaintiff’s attorney. Plaintiff’s counsel responds, “I will convey that to my client, but I cannot recommend it. I am prepared to recommend one hundred fifty thousand, however. I think I can convince my client to take that.” The truth is, I am actually authorized to offer up to one hundred thousand and the plaintiff’s attorney has probably already discussed with the client a bottom line number, which is likely below the one hundred fifty thousand for which they are asking. But we will go back and forth several more times before finally resolving the matter. I will lie about how much settlement authorization I have and the plaintiff’s attorney will lie about the client’s bottom line. That is how we get to “yes.”

I rationalized all of this on grounds that nobody was really being deceived. Every seasoned plaintiff’s attorney knows what a case is worth and will not settle it for less. The plaintiff’s attorney also knows very well that defense attorneys like me never put all our settlement authorization on the table in the first go-round. Defense counsel understand that a settlement demand is just an opener to get negotiations going. It is not a line drawn in the sand. Long before a case gets close to trial, both attorneys have a pretty good idea of the risks and exposure involved. They will resolve the case on that basis-or not. So what is the harm? Nobody is deceived and no one is getting hurt. If all this posturing gets us to a place where a dispute can be resolved without the risk and expense of trial, doesn’t the end justify the means?

However much the interests of our respective clients and the administration of justice might benefit from this process and the lying it entails, I still believe that there exists a mortal threat to the soul. The first case I settled left me feeling very ill at ease and, frankly, a little nauseated. Having been raised in a home where honesty was taught and expected, having taught and preached honesty from the pulpit for years, I was now horrified that I had willfully and knowingly practiced deceit by speaking untruths. The second case was easier. After a few more cases, I had become quite the natural when engaging in settlement negotiations. If I may say so, I got to be rather good at it. Thankfully, however, I never reached the point where I was at peace with it.

There is, I think, danger in becoming comfortable with lying, no matter how established a custom and practice of settlement negotiations it may be. If it is easy for me to lie in settlement negotiations, would it not become as easy for me to lie to my wife? Why not tell her that I am home late because I got caught up in traffic rather than reveal that I stayed late to have a drink or two with a couple of colleagues? My little fib will make her more sympathetic and less exasperated with me. That, in turn, will make for marital tranquility instead of strife. We will both enjoy a happier evening together. So what’s the harm? The harm is that the practice of lying becomes more pronounced and begins to spill over into all other aspects of one’s life. Once you become comfortable with lying, as soon as you get to the point where it comes effortlessly, where lying becomes a regular habit employed to avoid difficult and embarrassing confrontations, it spirals out of control. Lying begins to undermine your relationships, cloud your professional judgement and ruin your spiritual wellbeing. The truth becomes your dreaded enemy, always threatening to blow down the wall of illusions you have built around yourself. In the end, you wind up lying to yourself. The most dangerous lies are the ones we tell to ourselves about ourselves. When you have finally lost altogether the capacity to distinguish between the lies you tell and the truths you believe, you have fallen victim to a lethal moral pathology, a sickness of the soul that devourers the core of your being. You no longer know who you are. That is the end stage of the “way of death.”

I am thankful that throughout the period in my life during which I practiced law, I was also part of a community of truth tellers. As good as I may have gotten at the settlement game, my church’s preaching, teaching and example ensured that I never became truly comfortable with it. I was surrounded by people I knew would never let me get away with excuses, rationalizations and “alternative facts.” However good I may have gotten at lying, my fellow disciples saw to it that I could never be at peace with it. I can see now, if only in retrospect, how my community of faith steered me away from “the way of death” and kept re-directing me to “the way of life.”

Our rejection of God’s beloved Son should have, according the way and logic of death, resulted in God’s wrath and punishment. But God chose the way of life and forgiveness for us instead. For that reason, it is now possible for us to choose the way of life rather than remaining in death. It is now possible for us to stop hiding behind the lies we use to justify, excuse and rationalize our behavior. It is possible now to escape the cycles of vengeance and retribution driving our politics, twisting our religion and fueling our wars. It is now possible to be motivated by God’s wide open future instead of being shackled with chains of guilt, resentment and regret to our dark and constricted past. Jesus embodies a stark alternative to the way of death. The way of life is now before us. From dawn to dusk, the old way of death pulls us back while the new way of life calls us forth. Each step taken in this new direction builds character, shapes in us the mind of Christ and empoweres us for living faithfully in a dying world.

We need each other if we are to remain on the “way of life.” That is why Jesus prays that his disciples will be one just as he is one with God the Father. The way of death is always before us. We meet it at school, in the work place, within our homes and families. It is easier to turn away from one who is in need, shut the door in the face of strangers, opt for the easy lie instead of the difficult conversation, keep quiet in the face of injustice instead of speaking out for its victims. We need each other to remind each other that ours is the way of life, the way of our God who passionately loves our world and calls upon us to love our neighbors across the street and across the world. We need to support one another in the practices that build the mind of Christ among us.

Here is a poem/pray by Jan L. Richardson celebrating the freedom given us to choose the way of life.

In the center of ourselves

you placed the power

of choosing.

Forgive the times

we have given that

power away,

when we have sold

our birthright

for that which

does not

satisfy

our souls.

And so

in your wisdom

may or yes

be truly yes

and our no

be truly no,

that we may

touch with dignity

and love with integrity

and know the freedom

of our own choosing

all our days.

Source: Night Visions, Richardson, Jan (c. 1998 by Jan Richardson; pub. by Wanton Gospeller Press). Jan Richardson is an artist, writer, and ordained minister in the United Methodist Church. She grew up in Evinston, a small community outside of Gainesville, Florida. She is currently director of The Wellspring Studio and serves as a retreat leader and conference speaker. In addition to the above cited work, her books include The Cure for Sorrow, Circle of Grace, A Book of Blessings for the Seasons, In the Sanctuary of Women, and Sparrow: A Book of Life and Death and Life. You can learn more about Jan Richardson and her work on her website.