THIRD SUNDAY OF ADVENT

Prayer of the Day: Stir up the wills of all who look to you, Lord God, and strengthen our faith in your coming, that, transformed by grace, we may walk in your way; through Jesus Christ, our Savior and Lord, who lives and reigns with you and the Holy Spirit, one God, now and forever.

“Are you the one who is to come, or are we to wait for another?” Matthew 11:3.

John’s question seems reasonable. Last Sunday we met John at the banks of the Jordan River. The crowds were gathered about him. Everyone from the religious elite to the women of the street were listening intently to his announcement that the reign of God had drawn nigh, that One was coming soon who would level the proud and powerful, raise up the lowly and oppressed and redeem Israel. From rich to poor, righteous to reprobate, everyone it seems was streaming toward John for baptism.

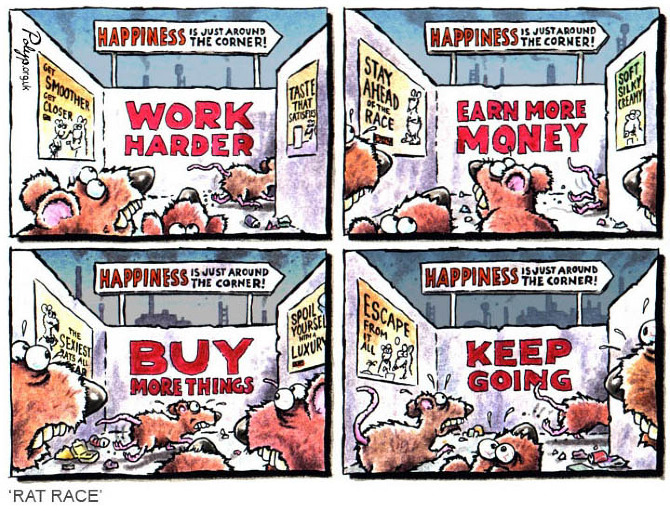

That was then. This Sunday we find John languishing in prison. The one John took to be “the One” seems a long way from bringing about the earthshaking transformation he was expecting and what he promised to his audience. Quite understandably, John wants to know whether and when Jesus is going to deliver. Is Jesus simply waiting for the right moment to “make his move?” Or has John been cruelly deceived? Did John, like so many people before him and so many people since, fall for a charismatic and persuasive personality who is all spectacle and no substance? Is Jesus really the one? Or should John, in the short time he has left, start looking elsewhere?

Sometimes it seems the church is expressing the same doubt about Jesus. A lot of what passes for Christianity these days, high church, low church, left wing, right wing, and all categories in between has little to do with Jesus. Lest anyone imagine that I am throwing stones across ecclesiastical lines, let begin with an example from my own ELCA. Toward the end of my ministry, I was attending a workshop sponsored by my church focusing on ways toward spiritual renewal for our congregations. For an hour and a half we engaged in exercises designed to stimulate conversation, discussion and strategizing for church growth. Toward the end of the meeting, one of the facilitators asked if we had any questions or comments about this proposed program. I raised my hand and asked the facilitator whether she was aware that not once during the entire process did the name of Jesus come up and whether that was inadvertent or intentional. (I thought about adding that I was not sure which answer would be the more disturbing). She did not have much of an answer. Another facilitator finally spoke up and said in a decidedly irritated tone, “I don’t think it is necessary to invoke the Trinity after every single paragraph.” (For the record, I do not recall any references to God the Father or the Holy Spirit either.)

I also find it intriguing that so many Christian activists are pushing to post the Ten Commandments in our nation’s classrooms, but not a single one that I know of is pushing for a posting of the Beatitudes. Moreover, while condemning same sex relationships on the basis of Leviticus 20:13, many of these same folks ignore Leviticus 19:34 admonishing Israel, “You shall treat the stranger who sojourns with you as the native among you, and you shall love him as yourself, for you were strangers in the land of Egypt: I am the LORD your God.” The latter is the verse Jesus lifts up in his Parable of the Last Judgement and identifies as one of the two “Great Commandments.” Matthew 22:37-39.

Admittedly, Jesus does not fit well into the religion of empire, the role into which it has been cast first by Rome and subsequently by the parade of kingdoms and nation states that followed. A messiah who admonishes his disciples not to resist violence with violence does not square with regimes claiming the right to extinguish human life in the interests of justice and national security. Christian ministers in the United States struggled throughout the 19th Century (and before) to find a doctrinal rationale for slavery. They found some ammunition in the Hebrew Scriptures where slavery, while subject to statutes insisting on the humanity of the enslaved and protecting their interests to some extent, nevertheless acknowledged slavery as part and parcel of the social order. These ministers also appealed to Saint Paul’s letter to Philomen where the apostle appears to acknowledge Philomen’s legal claim over his runaway enslaved servant, Onesimus. But references to Jesus in these arguments are noticeably absent.

Similarly, Jesus does not fit in well with our culture’s currents insisting on male dominance or their hostility toward feminism. That hostility has become increasingly evident under the current Trump regime that speaks directly to the fear and insecurity of men fearing the loss of their privilege. As I have noted previously, ground of uncontested manhood has been shrinking for decades and continues to disappear as women occupy more roles formerly monopolized by men. The role of the man as master of his household, protector of his spouse and uncontested ruler over his children no longer holds. Men find themselves in a world where brute strength is no longer met with awe, jokes that demean women are no longer funny and clever pickup lines no longer work. It is disorienting, to say the least and, to a large degree, threatening. When J.D. Vance ridicules “childless cat women” and complains that men find themselves unable to express themselves by telling a joke or holding the door for a woman, one cannot help but hear the frantic undertone of a disenfranchised man-boy crying “respect my penis, goddamit!”

Religious support for the reassertion of “traditional manhood” is not lacking. For example, in a recent book

Rev. Zachary M. Garris, pastor of Bryce Avenue Presbyterian Church (PCA) in White Rock, New Mexico writes in his recent book:

“Christianity is a masculine religion. Men have authority, and as go the men, so go the women and children. Yet we are facing a crisis of masculinity in the church. Men have failed to lead, including our pastors, and now our women are acting like men and our men like women. To recover from this crisis of masculinity, we must start with God the Father. We must start with worship. Christianity has a masculine message of a husband who laid down His life for His bride. But we have an effeminate church preaching an effeminate gospel, proclaiming Jesus as Savior while ignoring His command for male rule in His kingdom.” Zachary M. Garris, Masculine Christianity.

There is no “command for male rule” from Jesus. Again, while proponents of “muscular, he-man” Christianity and the subordination of women can cite a number of biblical passages in support of their assertions (and conveniently ignoring others that do not), they seldom (if ever) make any reference to Jesus. That is not surprising. Jesus had no interest in male claims of ownership and control over women. Indeed, he made clear that no such inequality has any place in the reign of God (See Matthew 22:23-33; Mark 12:18-27; Luke 20:27-40). In all four gospels the Resurrected Christ commissioned women as the first preachers to proclaims his resurrection. In all four gospels women are often the most perceptive to Jesus’ preaching and teaching. He frequently points to women as exemplars of the faith often lacking in the Twelve. (Matthew 15:21-28; Mark 12:41-44; Mark 14:3-9). Nowhere does Jesus suggest that there is a divinely established gender hierarchy either in nature or in the reign of God he proclaims.

The bottom line here is that disciples of Jesus read the scriptures through the lens of his obedient life, faithful death and glorious resurrection. Jesus teaches us that the two greatest commandments are to “Love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your mind, and with all your strength” and “to love your neighbor as yourself.” Mark 12:28-31; Matthew 22:34-40; Luke 10:25-28). On these commandments hang the interpretation of all the law and the prophets as far as disciples of Jesus are concerned. Matthew 7:12. Thus, if your reading of the Bible leads you to place your trust in anything less than the God and Father of Jesus Christ or instructs you to treat any person created in God’s image with less than empathy, compassion and good will, it is not a Christian reading of the Bible. Diversity, equity and inclusion are not the “woke” agenda of any political or religious group. They are just plain Jesus. If that gores your political ox, get yourself another politics or another savior.

So John’s question remains: Is Jesus the one? Or should we look for leaders who are more pragmatic, more result oriented and more prepared to employ any means to a noble end? Is the gentle, peaceful and faithful way of Jesus in a cruel and violent world the way to a new creation? Or should we listen instead to those who tell us that you cannot make an omelet without breaking a few eggs? That the burden of caring for the blind, the lame and the sick is too great a strain on the national budget? Is the Sermon on the Mount meant only for neighbors with nothing between them but white picket fences and ill suited for the rough and tumble life of business, politics and geopolitical conflicts? Or is the Sermon a template for the life Jesus actually lived in a hostile world that finally took the shape of the cross, the same life to which he calls his disciples?

Note well that Jesus does not give John a direct answer to his question. Instead, he instructs John’s messengers to tell John what they have seen: “the blind receive their sight, the lame walk, those with a skin disease are cleansed, the deaf hear, the dead are raised, and the poor have good news brought to them. And blessed is anyone who takes no offense at me.” Matthew 11:5-6. That is where we need to look. We need to turn our gaze to the southern border where faithful disciples of all traditions and other people of good will are caring for, advocating on behalf of and supporting refugees caught in the hellish no man’s land of detention camp life. We need to look toward those churches that are fighting for the rights of medical access for transgender children who have become victims of our government’s ideology and policies of hatred. We need to look at communities of faith all over the world whose faithful work and witness are opening blind eyes, lifting up those who cannot stand on their own and bringing a measure of healing to the sick and abandoned. Some will take offense at this good work, insisting that it is wasted. Others might dismiss it as too little, too late and too ineffective to make any real difference. Disciples of Jesus recognize them as signs of God’s inbreaking reign, trickles of water leaking through the dam. Today they look small and inconsequential. But they are signs that the dam of oppression and injustice is cracking and destined to break and, when it does, there will be no stopping the ensuing flood.

Here is a poem by Laura Hershey giving voice to the blind, lame and sick, frequently seen as “social problems” in our culture, but for whom Jesus proclaims liberation, healing and “good news.” Blessed are those who take no offense.

Special Vans

The city’s renting special vans,

the daily paper reads,

The cops are getting ready,

for special people with special needs.

The mayor’s special crip advisor

has given special training

in moving all our special chairs

when arresting and detaining.

They’ve set up special jail cells

in a building on the pier.

They’ve brought in special bathrooms

and nurses—never fear.

The cops are weary of our bodies

they treat us in a special way,

special smiles, if you’re lucky

special brutality when you’re in the way.

Bush’s campaign office gives us

all the special treatment we can take;

locked doors and angry words,

while Clinton’s office gives us cake.

The ones who run the nursing homes

think they’re doing noble deeds—

locking up our friends in cages

special people with special needs.

They put up special barricades,

to try to keep us out,

still we’re in their face,

still we chant and shout.

What’s so special really

about needing your own home?

If I need pride and dignity,

is that special, just my own?

Are these really special needs,

unique to only me?

Or is it just the common wish,

to be alive and free?

Source: Laura Hershey: On the Life & Work of an American Master (Unsung Masters Series, 2019). Laura Ann Hershey (1962–2010) was a poet, journalist, feminist and a disability rights activist. Hershey was a leader of protests against the paternalistic attitudes and images of people with disabilities inherent to Jerry Lewis’s MDA Telethon. She was known to have parked her wheelchair in front of buses to bring attention to the rights of those labeled “disabled.” Hershey was a regular columnist for the Christopher and Dana Reeve Foundation. She published on her own website, Crip Commentary, and was published in a variety of other magazines and websites. Hershey was admired for her wit, her ability to structure strong arguments in the service of justice and her spirited refusal to let social responses to her spinal muscular atrophy define the parameters of her life. She was also the mother of an adopted daughter. You can read more about Laura Hersey and sample more of her poetry at the Poetry Foundation Website.