FOURTH SUNDAY IN LENT

Prayer of the Day: Bend your ear to our prayers, Lord Christ, and come among us. By your gracious life and death for us, bring light into the darkness of our hearts, and anoint us with your Spirit, for you live and reign with the Father and the Holy Spirit, one God, now and forever.

“If you were blind, you would not have sin. But now that you say, ‘We see,’ your sin remains.” John 9:41.

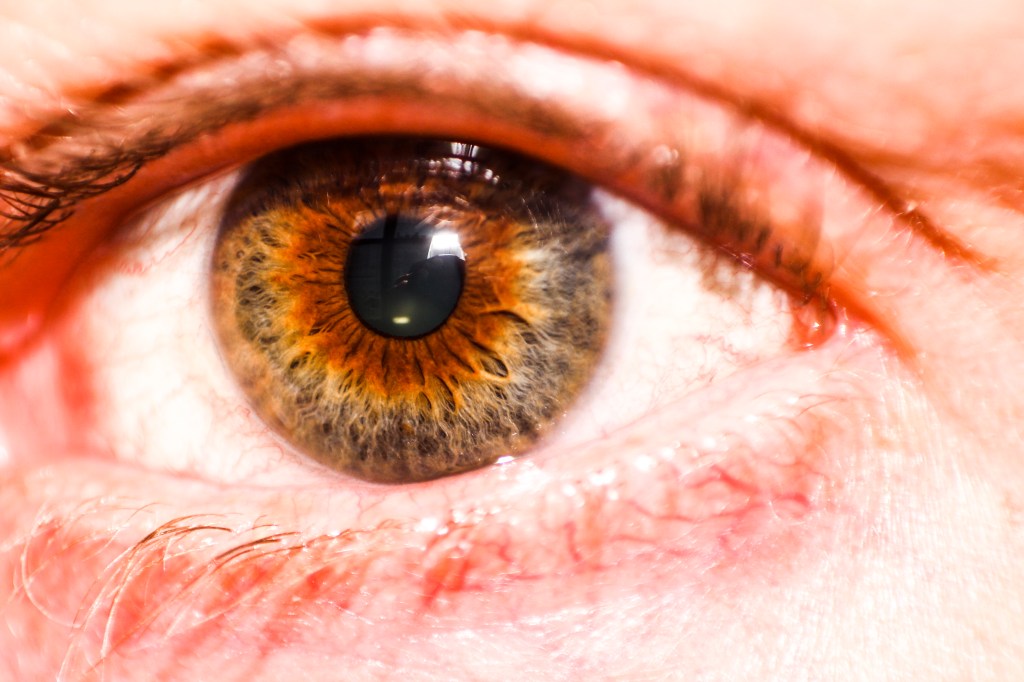

According to Jesus, there is more to blindness than simply lack of sight. In fact, even a person born blind is capable of sight, while those with perfectly sound eyes can be utterly blind. The disciples were blind to the humanity of the man Jesus encounters in our gospel lesson, a man who managed against the odds to survive without sight in a world without a safety net for the disabled. To the disciples, this man was an abstraction, a theological riddle to be solved with sophistic arguments. Surely a good and gracious God cannot be responsible for such a dreadful circumstance as congenital blindness. “So what do you think, Jesus,” the disciples ask. “Who sinned, this man or his parents?” The disciples saw the man born blind with their perfectly sound eyes, but not with their hearts.

This kind of thinking is not unusual. Although we enlightened moderns are not inclined to attribute the misfortunes of others to divine wrath, we are often quick to attribute their suffering to some mistake, misstep or bad judgment on their part. In fact, there is a tendency to take perverse satisfaction in pointing out how easily the tragedies of others could have been avoided. “What was he thinking of, going into a neighborhood like that in the dark of night?” “What did she expect was going to happen, going to a frat party in that skimpy outfit?” “If he had thought for a single minute before answering that text, he would have recognized it as a scam.” I expect there is more than just meanness at work here. It is, after all, comforting to believe that we live in a universe where wise, good and prudent conduct is always rewarded and foolish, wicked and careless behavior punished. Such belief allows us to indulge in the delusion that we are safe from injury, tragedy and untimely death-if only we practice good sense and a modicum of decency. It blinds us to the reality that our world actually is one in which bombs incinerate teenage girls whose only crime was coming to school; tornados rip through towns leveling indiscriminately both churches and brothels; terminal cancer, starvation and violence afflict innocent children while vicious war criminals live into their nineties and die in peace.

Living in the light, as Jesus calls us to do, forces us to see things to which we might rather remain blind. Witness president Trump’s recent failed attempt to remove from President’s House in Philadelphia an exhibit that honored the lives of the nine people held there who were enslaved by President George Washington. Desperate to maintain the false mythology of a pure and virtuous America and its white founders, many among us would simply erase from our history the terrible legacy of slavery, Jim Crow and ideological racism. We prefer living in the darkness of comforting lies rather than in the harsh light of truth.

There is a price to be paid, however, for such willful blindness. The real world, with all its unpredictable catastrophes, random tragedies and undeserved suffering affords those with eyes to see it opportunities to “work the works of [God] who sent [Jesus].” John 9:4. But for those who choose to remain in the false security afforded by what Jesus calls “darkness,” such opportunities remain forever out of reach. Blindness of willful complacency blunts the capacity for empathy and compassion, thereby deforming our humanity and preventing us from seeing with our hearts. This, not a mere infraction of some moral or religious code, is the biblical understanding of sin. Sin, according to Jesus, is the dangerous habit of willful blindness. It is a refusal to see what makes one uncomfortable, what challenges what one thinks one knows, what invites one into a larger understanding of what it means to be fully human. Jesus does not bother entertaining the disciples’ theoretical questions about the cause of the man’s blindness. Instead, he acts with compassion. He opens the blind man’s eyes and, in so doing, opens the spiritual eyes of his disciples. Unlike the disciples, Jesus sees the man born blind with his heart.

I have had to have my eyes opened numerous times throughout my life. I have had to learn over and over again to see not merely with my eyes, but with my heart. Through my wife’s debilitating injuries, I have come to a new realization of how thoroughly our society excludes persons with mobility challenges from full participation in our common life. Though it has been twenty-six years since the passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act, numerous barriers to restaurants, doctors offices, municipal buildings, places of worship, museums, beaches and public parks remain, preventing or making it difficult and dangerous for persons with mobility challenges to access essential services as well as recreational resources-which they support with their taxes as much as the rest of us. In traveling with Sesle on the slow, difficult road of recovery and adaptation, I have learned to see public buildings of all kinds in a new way. I see now the barriers, obstacles and obstructions that make a mockery of signs reading “welcome.” I am also increasingly mindful of others experiencing difficulty with these barriers and opportunities for offering assistance. That to which I was once blind, I can now see.

What will it take to open our eyes? What difference would it make if we could see the Iranian school girls killed by our bombs, not as inevitable “collateral damage,” but as the daughters of dads who beamed with pride as they watched them recite their prayers, moms who dressed them, brushed their hair and sent them off to school with no clue they would never see them again. What difference would it make if enough of us saw the 350,000 Haitian refugees the Trump administration is desperately seeking to deport, not as a mere number, but as parents seeking the same safe environment we seek for our children, young people longing for the opportunity to get a basic education, families who wish only to live free from the scourge of gang violence? What difference would it make if we could see all people with our hearts through the eyes of Jesus?

Here is a poem by Howard Nemerov speaking to the willful blindness against which Jesus warns us and from which he would liberate us.

The Murder of William Remington[1]

It is true, that even in the best-run state

Such things will happen; it is true,

What’s done is done. The law, whereby we hate

Our hatred, sees no fire in the flue

But by the smoke, and not for thought alone

It punishes, but for the thing that’s done.

And yet there is the horror of the fact,

Though we knew not the man. To die in jail,

To be beaten to death, to know the act

Of personal fury before the eyes can fail

And the man die against the cold last wall

Of the lonely world—and neither is that all:

There is the terror too of each man’s thought,

That knows not, but must quietly suspect

His neighbor, friend, or self of being taught

To take an attitude merely correct;

Being frightened of his own cold image in

The glass of government, and his own sin,

Frightened lest senate house and prison wall

Be quarried of one stone, lest righteous and high

Look faintly smiling down and seem to call

A crime the welcome chance of liberty,

And any man an outlaw who aggrieves

The patriotism of a pair of thieves.

Source: The Collected Poems of Howard Nemerov (c. 1977 by Howard Nemerov, pub. by The University of Chicago Press). Howard Nemerov (1920-1991) was an American poet. He was twice Poet Laureate Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress, from 1963 to 1964 and again from 1988 to 1990. He also won the National Book Award for Poetry, Pulitzer Prize for Poetry, and Bollingen Prize. Nemerov was raised in New York City where he attended the Society for Ethical Culture’s Fieldston School. He later commenced studies at Harvard University where he earned his BA. During World War II he served as a pilot in the Royal Canadian Air Force as well as the United State Air Force. He was honorably discharged with the rank of Lieutenant and thereafter returned to New York to resume his writing career. Nemerov began teaching, first at Hamilton College and subsequently at Bennington College and Brandeis University. He ended his teaching career at Washington University in St. Louis, where he was elevated to Edward Mallinckrodt Distinguished University Professor of English and Distinguished Poet in Residence from 1969 until his death in 1991. Nemerov’s poems demonstrated a consistent emphasis on thought, the process of thinking and on ideas themselves. Nonetheless, his work always displayed the full range of human emotion and experience. You can find out more about Howard Nemerov and sample more of his poetry at the Poetry Foundation website.

[1] William Walter Remington (1917–1954) was an American economist who was employed in various United States government positions. His career was interrupted by accusations of communist espionage made by Elizabeth Bentley, a Soviet spy and defector. Remington was tried twice and convicted twice. The first conviction was set aside on legal grounds, but the second conviction on two counts of perjury was upheld. He was sentenced to three years in federal prison. In November 1954, he was murdered in his cell by fellow inmates at Lewisburg Prison.